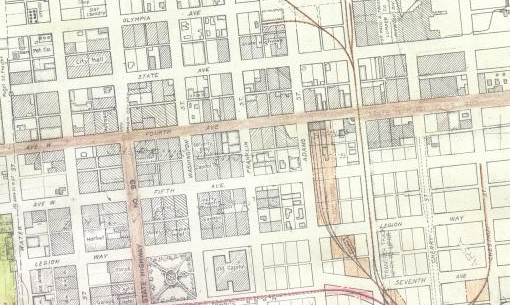

The layout of downtown Olympia is burned into my brain. It just seems inherent to the space that coming down from the Upper East Side, both State and 4th are one-way. Especially coming from my neighborhood, this doesn’t always make 4th and State the fastest way across town. But it does feel like it’s always been this way, that when we created this part of town, the original layout was two paired one-way streets.

But that’s not actually true. Before the late 40s, downtown was just a normal grid. You could go both ways on every street.

The switch to one-way streets wasn’t some long-planned city project either. It was an accident caused by a massive earthquake in 1949. What started as a quick fix to get around piles of fallen bricks turned into a permanent setup. Then the state highway department saw an opening to turn our local streets into a highway for commuters, and they took it. It’s a classic case of prioritizing fast cars over a walkable neighborhood.

Before 1949, Olympia’s downtown felt a lot tighter and more connected. We didn’t have all these massive parking lots everywhere. Instead, it was just row after row of actual buildings. This was also when the residential neighborhoods surrounding downtown were interconnected using similar grid patterns, before growth had grown beyond Division on the west and Boulevard on the east.

When a street goes both ways, twice as many people see a storefront. You aren’t “eclipsed” by the direction of traffic. But after WWII, engineers became obsessed with “throughput.” They stopped thinking about downtown as a place to be and started seeing it as a hurdle to drive through. They wanted to move the tides of cars as fast as possible. The old two-way grid was standing in their way, but it took a disaster to finally break it.

The real turning point happened on April 13, 1949. It was just before noon when a 7.1 magnitude earthquake hit. It was the biggest one the region had seen all century. Two people died, and the damage was immense. Eleven buildings were so damaged that they had to be boarded up immediately.

4th Avenue and State Street were a mess. To keep things moving while crews cleaned up the rubble, the city made a quick call: make them one-way. It was supposed to be a temporary fix to manage the chaos. But the streets never went back to the way they were. The earthquake gave engineers the perfect excuse to push a one-way vision that had been bubbling under the surface for years.

By late October, downtown business owners were joining forces to ask for a return to the pre-April alignment downtown. “Promises were made to return to two-way traffic as soon as the emergency was relieved,” said a downtown druggist and head of a business committee.

This is where the State Highway Department really left its mark. As the city debated whether to keep the temporary measure through the fall of 1949, the state didn’t just suggest keeping the one-way streets; they basically mandated it. They decided to fold 4th and State into the state highway system. 4th Avenue became the southbound lanes for the Pacific Highway, and State Avenue took the northbound traffic.

The legislature had passed a law the year before, allowing the Highway Department to take a heavier hand in ensuring state highways efficiently passed traffic. To that end, the highway department studied the issue of now one-way streets in Olympia and gave the city government two options: stay with one-way or lose all the parking along 4th and State.

By doing this, the state prioritized regional travel over the people actually living in Olympia. The main goal was throughput, moving people from the suburbs to their jobs or across the state as fast as possible. Our downtown streets weren’t local roads anymore. They were effectively a highway split in half. Once that highway designation was set in stone, there was no going back. The state had its high-speed corridor, and the city was stuck with the noise and the speed.

Business leaders talked about suing, saying the state was taking too heavy a hand. But no lawsuit followed, and downtown settled into its current pattern. Just less than 10 years later, Interstate 5 bypassed downtown Olympia, but one-way streets stayed.

We’re still paying for that 1949 decision today. On paper, one-way streets move cars fast, but they make life harder for everyone else. Research shows that child pedestrians are 2.5 times more likely to get hurt on one-way streets. It makes sense if you think about it. Drivers get into a highway mindset and stop looking for people.

Looking back, the 1949 earthquake broke the way Olympia functions. We traded a walkable, easy-to-navigate downtown for a system that treats downtown like a bypass. This isn’t even getting into the number of buildings that were torn down in the last 75 years to make way for parking.

I focus a lot of attention on downtown Olympia in this discussion. But it is worth pointing out that most of the mileage for the one-way streets in Olympia goes through formally residential neighborhoods. The city has slowly changed how the blocks are treated around the one-way paired throughfairs, but to me, even if we build denser, mixed-use neighborhoods up the Eastside hill, slower, more people-oriented traffic orientation makes sense as well.

Today, plenty of cities are realizing this was a mistake. They’re converting one-way streets back to two-way streets to lower crime, help local businesses, and stop the constant speeding. It makes you wonder what Olympia would look like if we had just cleared the 1949 debris and stayed the course with our original grid. We might have had a downtown that feels more like a community and less like a race track.

Excellent research. I was aware 4th and State were originally two ways but had no knowledge of the earthquake and Highway Department’s involvement in the conversion to one ways. I can think of few projects that would benefit downtown Olympia as much as restoring 4th and State back to their original two way designs. These streets are guaranteed to remain unsafe as one way streets. In fact, they are guaranteed to grow increasingly unsafe as total vehicle miles traveled in the US continues to increase by approximately one percent each year. It’s simple arithmetic. More cars on already unsafe roads equals more carnage.

Thanks for explaining this history, as always. Just as a counter-perspective I’ll say that the presence of one way streets isn’t in diametric opposition to a pedestrian-oriented space. I definitely don’t think they make pedestrians safer or feel more secure, what with the higher speed of traffic. However, I would argue that because they create a greater efficiency for moving on foot as compared to in a vehicle, they create the perception of greater flexibility and ease of transport by walking. Though I’ve heard the view expressed, I’ve never felt that Downtown is a totally auto-oriented area. Having one way streets makes it harder for cars to get to certain destinations, ones to which pedestrians can easily navigate.

It’s definitely vexing that the system was implemented to shuttle cars through, and not to, downtown. I don’t really know what else could work though. You could look at a place like Port Townsend, which seems to thrive with a single entry/exit road with one lane in each direction. I can’t see that working out here though, given the amount of traffic already present along the one way couplet. Those cars would probably disperse onto other streets at peak hours, if the flow was redirected back to two directions, and it would probably result in downtown being gridlocked at peak hours, which isn’t conducive to a pleasant environment.

Of course, it would be nice to have fewer cars passing through Downtown, and maybe changing the infrastructure that makes the current traffic volume possible would in turn reduce traffic volume. I don’t know how much it should be considered, but I don’t think the change would be smiled upon outside of inner Olympia, and it would exacerbate the divide between opinions of Downtown, and maybe reduce visitation. I wouldn’t personally hate that, but it’s hard to argue that it would be a good consequence.

Perhaps raised crosswalks along 4th and State would do something in terms of slowing traffic, and make pedestrians the focal point. As I consider that, I see how one might then conclude that we might as well turn them into two-way streets, since the ultimate goal would be to slow down traffic. But that would overlook how beneficial it is to bus service, as the primary express corridor for Intercity Transit runs along the one way couplet. I agree that it seems like we’d be in a much better spot now if the streets had been reopened as they were before, back in 1949. I’m just not convinced changing it now accomplishes that much. What we really should do is go back to streetcars transporting people downtown. Don’t ask any economists about that idea.

One way streets with more than one lane are almost always less efficient for pedestrians compared to two way streets. Certainly that is true of 4th and State, both which prioritize car traffic efficiency above all else, at the loss of efficiency (and safety) of multimodal road users.

One way streets are not inherently bad. But 4th and State are extremely poorly designed and unsafe for all road users including drivers. The only way those two particular streets can realistically be made safe as one ways is to reduce each street to one lane (or two lanes each with one lane of each street dedicated solely to buses and bikes).

As a full time pedestrian who walks a few thousand miles in Olympia each year, I don’t ever walk on 4th or State because they waste my time and drastically increase my probability of being injured. I will take traffic congestion any day of the week on these streets rather than the wasteful lunacy that exists today.

Alright, I actually love the idea of converting one of the lanes on each of 4th and State to bus/bike. I’m not sure how it would work exactly, but I think that would be a really nice compromise and would better reflect Olympia’s values than the current layout.

I respect that choice to not walk on 4th and State based on probability of serious injury; it makes a lot of sense to avoid them for that reason. I actually feel differently about it, though. I feel a lot more secure walking along the parking-separated sidewalk of a one way street than I do on the average two-way street.

I guess for me, though I understand that there’s statistically a greater risk from walking on high speed streets, the security of only having to worry about one direction of traffic, and the presence of space between the car lanes and sidewalk, make it preferable to walk along 4th and State to, say, a two-way street like 5th Ave, or Boulevard Rd. Obviously, a lower traffic street is usually preferable.

But these psychogeographical insights don’t necessarily matter, except in revealing unquantifiable abstractions. What ultimately matters is what’s going to be the safest and most efficient for the most people. So, I think you and Mr. O’Connell are probably on the right track with this from a statistical perspective, although I haven’t looked at the data to know for sure.