For a city obsessed with moviemaking and modern narrative, the documentary Los Angeles Plays Itself works as a surprisingly effective local history of Los Angeles and Southern California. Much of how we understand Southern California arrives through the lens of filmmakers.

The core thesis of the documentary Los Angeles Plays Itself (or at least the one that rings truest to me) is that Los Angeles is constantly captured while being denied the ability to express itself. Even calling Los Angeles “LA” flattens the city, stripping away its complexity. It’s the cinematic equivalent of a typecast actor trying to communicate something real about themselves while trapped in someone else’s script.

My favorite thread in the film is its discussion of mid-century modern Southern California homes, so often repurposed as villainous lairs. Filmmakers turn a distinct and beautiful regional architecture into something cold, cruel, and hostile, warping the meaning of the place itself.

This is the inverse of the problem Seattle (and the broader Pacific Northwest) faces.

Just a note before I go any further: I acknowledge “Seattle” isn’t synonymous with “the Pacific Northwest.” I use it as a stand-in for the urban Northwest, which also includes Portland, parts of Tacoma, Bellingham, and Olympia. There is a broad spectrum of society that is centered deeply in the Seattle experience. There isn’t a moat around the city, so what happens there matters elsewhere. I just wanted to acknowledge that there are missing pieces to what I’m writing about today. Which is sort of the meta-point of the essay anyway.

So, moving on.

Unlike Los Angeles, which plays every city or no city at all, other cities almost always play Seattle. And what this does is it keeps us from approaching our own story. The story necessary for film keeps our own story to one side.

Films set in Seattle routinely shoot somewhere else. Fifty Shades of Grey was filmed in Vancouver, the most common “not Seattle.” More cruelly, The Boys in the Boat was filmed mostly in England, where a historic England market town and a primary school stood in for the Depression-era University of Washington and Seattle.

The first question is whether we can forgive Vancouver as it stands in for Seattle. Both belong to the proto-nation of Cascadia, sibling cities separated by an inconvenient international border. That logic almost works, except Vancouver suffers from its own Los Angeles Plays Itself problem. It plays everyone.

Vancouver has appeared as San Francisco (Rise of the Planet of the Apes), New York (Life or Something Like It), Chicago (I, Robot), Tokyo (Godzilla), and Shanghai (Code 46). It has even played fictional cities like Metropolis (Smallville) and Gotham (Batwoman).

Seattle, by contrast, rarely gets to play itself. When it appears on screen, it matters more as an idea than as a physical place.

Seattle functions cinematically as a concept rather than a geography or community.

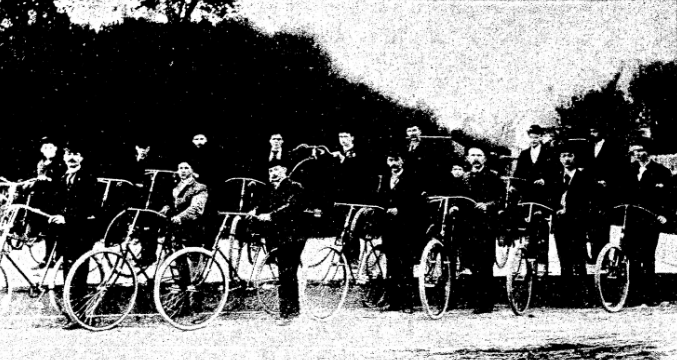

The city became shorthand for the foggy shape created when you pull together grunge, Starbucks, and Tech: cultural exports that transformed Seattle into a symbol of urban aspiration and fantasy. As James Lyons explains in Selling Seattle, the city’s rise in film and television accelerated in the early 1990s as it shed its identity as a “rough diamond” lumber town (itself very limiting) and rebranded itself as a center of technology and culture.

One reason filmmakers gravitated toward Seattle was its portrayal as a “safe haven” and “white oasis” for middle-class professionals, especially when contrasted with the media narratives of urban decay and racial unrest that defined Los Angeles in the same era.

Nora Ephron’s Sleepless in Seattle (1993) cemented this version of the city: sentimental, romantic, and largely frictionless. Young-ish professionals move through a city unburdened by history, class, or social constraint, living urban-adjacent lives without consequence.

The grunge subculture added a layer of “novel edginess” that appealed to filmmakers without pushing into our actual history or non-white communities. Coffee shops and music venues signaled bohemian credibility while remaining safely contained. Seattle became a metropolitan sanctuary, a cool, mist-covered stage balancing high-tech ambition with rugged natural isolation.

This mythology formed the mental backdrop for stories set in Seattle, but not of Seattle.

Half Steps in Popular Film

The films that do get Seattle and the Pacific Northwest better, if not correct (Singles, Grassroots, The Ring, and the very recent Train Dreams), do so largely because they were filmed here. They often show a different city and region than the friendly, white, urban unicorn of popular imagination.

The Seattle of Singles is jaded and two-faced. In Grassroots, the city turns up its nose at dreamers, favoring politically “serious” projects like light rail over visionary but impractical ideas like the monorail. The Ring forces viewers to confront how dark it gets here (literally and metaphorically) and how much remains unseen. Train Dreams expands the frame beyond the city entirely, emphasizing the overwhelming scale of Pacific Northwest nature, the nature of transitory communities, and asking viewers to sit with uncertainty until the very end.

These films start to reveal what we lose when Seattle doesn’t get to play itself. Nowhere is that loss clearer than in the limitations of Grassroots.

Grassroots feels faithful in spirit, but only if you squint. Adapting Phil Campbell’s memoir, Zioncheck for President, required sanding down something far darker and more unstable. The resulting film is earnest and encouraging, the kind of story that makes local politics feel charming.

Campbell tells the story of Marion Zioncheck, a brilliant, erratic, and tragic 1930s Seattle congressman. He weaves Zioncheck’s life through the 2001 monorail campaign, framing it as a ghost story about Seattle radicalism and its costs. The memoir isn’t really about a monorail or a doomed campaign; it’s about the thin, dangerous line between political idealism and clinical instability.

Removing Zioncheck loses the story’s historical ballast and its most unsettling question: whether Grant’s obsession represents visionary persistence or the modern echo of a tragic mental break, and how Pacific Northwest political culture absorbs and romanticizes both.

The book also lingers on the unease beneath the framing of two white, slacker-intellectuals trying to unseat one of the city’s few Black political leaders. Campbell confronts the ugliness of that tension, questioning how grassroots movements often remain blind to their own privilege and moral certainty. The film acknowledges this dynamic, then quickly retreats to the cleaner abstraction of monorail versus light rail, choosing policy debate over racial and class friction.

Grassroots reads as a love letter to civic engagement in Seattle. Zioncheck for President feels messier and truer, a beautiful, sometimes horrifying autopsy of a midlife crisis unfolding in public. Both love the city, but only one sits with what that love costs and what it reveals about Seattle itself.

This may simply reflect the limits of film versus books, something a smarter person could explain more elegantly. Books allow for nuance that even a three-hour movie struggles to sustain. Film demands loss. A loss that text can afford to keep.

So maybe we’re stuck if we focus only on film.

Broader Narratives

Supersonic and West of Here are two sweeping novels that attempt to wrap in more faithfully the missing context that a true narrative of the Pacific Northwest brings to the table.

But books like Survival Math by Mitchell S. Jackson and No-No Boy by John Okada cut deeper, peeling back the familiar Pacific Northwest mythology of tech, evergreen cutaway shots, and coffee-fueled progressivism in a white space. They reveal a regional story shaped instead by displacement, survival, and the hard geometry of who gets to belong.

Supersonic and West of Here gesture toward these realities, but they stop short of plunging into the disphotic zone of regional narrative.

No-No Boy’s Seattle looks nothing like the Emerald City of boosterism and nostalgia. The postwar International District barely breathes. Streets like Jackson become psychological checkpoints rather than simple routes. The protagonist moves through the city as an intruder, hyper-aware of his body, his history, and his perceived betrayal. The city doesn’t welcome him back; it watches him, measures him, reminds him that reintegration is conditional.

Jackson’s Portland in Survival Math stands as the inverse of the Portlandia fantasy. It isn’t quirky, gentle, or ironic. It is a city designed, architecturally and socially, to contain, monitor, and discard Black residents.

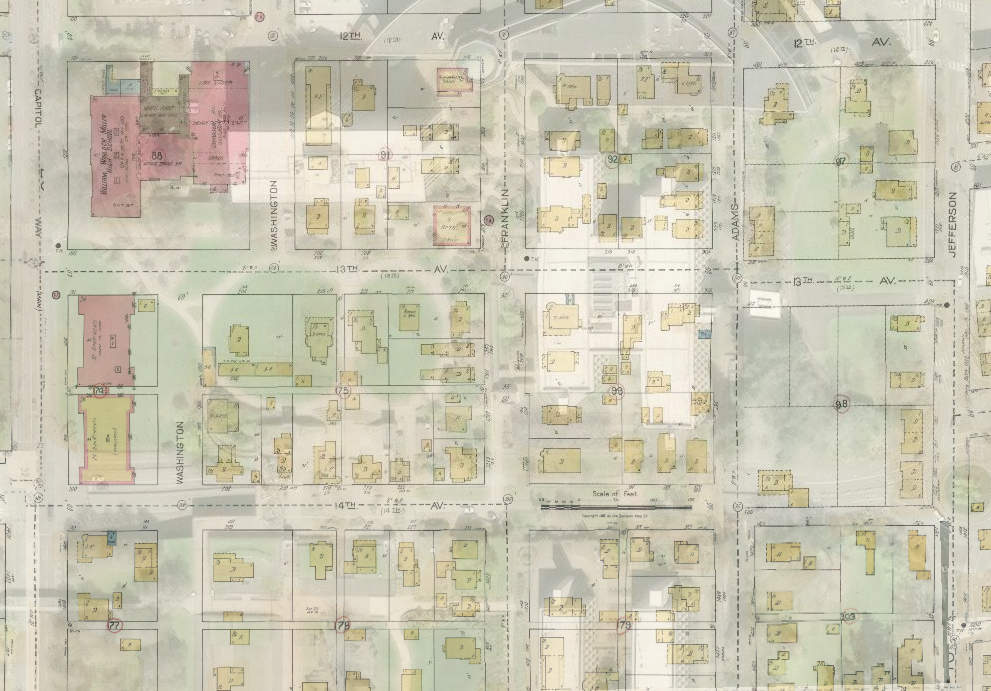

If the cinematic Seattle of the 90s was a “white oasis,” Zia Mohajerjasbi’s Know Your Place gives us the irrigation system, the grueling, uphill labor required to sustain a life in the cracks of the “urban aspiration.” Telling the story of an Eritrean-American teenager on an odyssey across the hills of the Central District to deliver a suitcase of medicine, the film allows the physical geography of the city to sync with the lived experience of marginalized inhabitants. Know Your Place doesn’t settle for the postcard views of the Space Needle that serve Grey’s Anatomy. Seattle is not a “safe haven” but a labyrinth of disappearing landmarks and a society that doesn’t serve everyone.

In Know Your Place, Survival Math’s displacement becomes visual. We see historic Black and immigrant-owned spaces not as footnotes, but as a vibrant, fragile reality being physically overwritten by the expanding white footprint. Like No-No Boy, the film uses the city’s verticality to illustrate social friction. Every hill climbed in Know Your Place is a reminder of the economic and systemic weight carried by the main character. By centering the East African community, the movie moves past the novel edginess of grunge to find the actual city, a complex, multi-layered heritage waiting for a lens.

Seattle Knows Itself

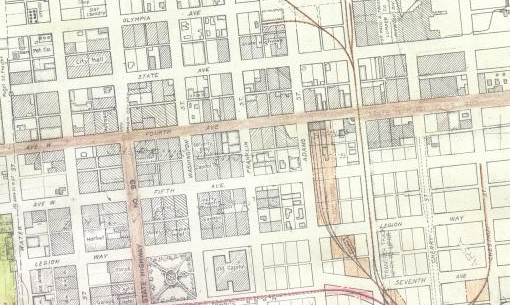

So, in a genre I know better (local history), this is Megan Asaka’s Seattle from the Margins as compared to Murray Morgan’s Skid Road. The quirky, mostly white, working-class history of Morgan’s Seattle presents the anti-Chinese 1886 riots as a dramatic, chaotic, and shameful moment of civic breakdown. Morgan uses his wit to describe the “vigilante” committees and the “horrible friendliness” of the mob herding people onto ships. However, he treats the event as a temporary fever, a singular eruption of “hate” in an otherwise colorful, rough-and-tumble town.

The deeper truth, explained by Asaka, is that the riots were a symptom of a deeper design of Seattle that kept non-white communities in Seattle on the margins.

The difficulty Seattle faces in cultural representation is still the inverse of Los Angeles’s problem: while LA is constantly filmed but denied self-expression, Seattle rarely gets to play itself. Instead, Seattle serves as a cinematic concept that erases our deeper understanding of our own place and our own history. The baggage that white people carry from across the country lands on our regional narrative when they use Seattle to tell stories or to move here.

This preference for the abstraction of grunge, Starbucks, and tech aspiration over geography warps the city’s narrative, overlooking its historical complexity and marginalized communities. But recently, we are seeing films that sync the city’s physical and social terrain with the lived experience of those on the margins.