There’s something about a neighboring city moving into nearby unincorporated neighborhoods that always gets people excited and wanting a city of their own. At least around here.

That’s exactly what happened in the 1960s when Lacey became a city.

The Birth of Lacey: A Rivalry with Olympia

Lacey’s path to cityhood was shaped by a rivalry with Olympia over annexation and control of fast-growing suburbs.

After World War II, Lacey shifted from farmland to a booming suburb, helped by projects like South Sound Mall. By the early 1960s, Olympia began pushing east, annexing land along Martin Way and Pacific Avenue up to Lilly Road. This sparked a “border war” as Lacey moved to incorporate and protect its own boundaries.

Lacey’s first incorporation vote in 1964 failed, but a second vote in November 1966 narrowly passed by about 200 votes. Almost immediately, conflict reignited. Residents of Lacey’s western “Olympia fringe area,” who had opposed incorporation, voted to leave and join Olympia in early 1967. Lacey sued to block the move, but courts upheld Olympia’s annexation under an old 1890 law (later changed in 1969).

That same year, voters in both cities considered merging into one. Supporters said it would cut costs, improve planning, and solve Lacey’s sewage problems by tapping Olympia’s system. The proposal failed, badly in Lacey, where residents strongly opposed merging.

The 1980s: Lacey Looks North to Puget

In the ’70s and ’80s, Lacey tried to annex eastward but hit resistance from established neighborhoods like Tanglewilde and Thompson Place. Much like Lacey in the ’60s, these neighborhoods didn’t want to join a bigger city, or form their own. They already had regional fire services, and Tanglewilde even formed its own park district, building the county’s only public pool.

So Lacey looked north, toward undeveloped land between those neighborhoods and Hawks Prairie.

During the 1980s, Lacey took an aggressive annexation strategy, focusing on big undeveloped areas with huge growth potential, like Hawks Prairie. This land promised billions in development and tens of thousands of jobs over two decades. Lacey wanted to bring in sewer, water, and other urban services while avoiding the political headaches of older neighborhoods.

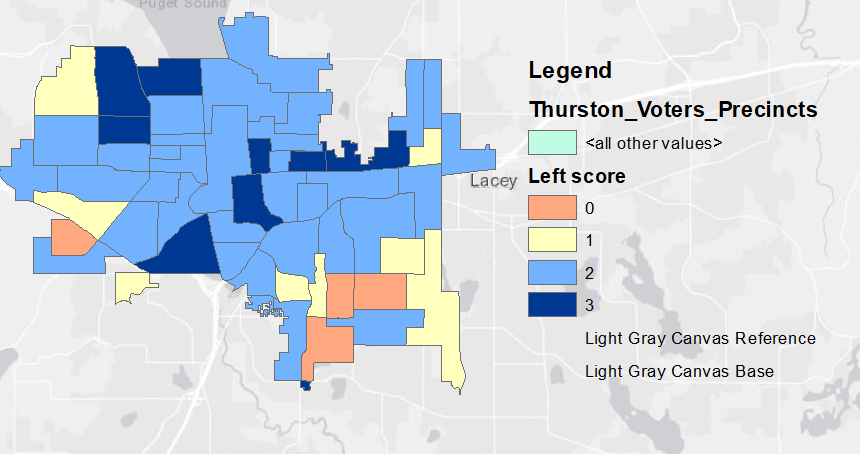

At the same time, Lacey played defense. It annexed strategically to stop the proposed City of Puget, an effort by rural residents to block Lacey’s expansion. Just like Lacey vs. Olympia before it, the Lacey vs. Puget City battle took on the same tenor of trying to keep the neighboring big brother from taking over.

The proposed City of Puget was named after an unrealized metropolis on Johnson Point. Puget City was platted in 1870 (and promptly un-platted three years later) as a possible terminus for the railroad. There are actually a handful of homes that sit on “Puget City” parcels in the area, but obviously, the rail road city was never built. As Lacey started their march to the inland sea in the 1980s, rural residents staked their own claim and petitioned the boundary review board for the creation of the 3,000 person City of Puget.

The new city idea died after the Boundary Review Board voted it down 3-2. The board leaned on a rift between residents of the rural areas and developers and residents of larger planned neighborhoods that wanted Lacey’s services.

One big difference between the 1960s and the 1980s? The Boundary Review Board. Created in 1967, these boards added consistency to city formations and annexations. You can’t rewrite history with “what ifs,” but it’s interesting to imagine what Lacey’s future would’ve looked like if it had been blocked like Puget.

Ultimately, Lacey annexed thousands of acres, leapfrogging older neighborhoods to build new subdivisions and warehouses. Those skipped-over neighborhoods fought off annexation attempts for decades, and now, in 2025, Lacey is looking back at them again.

But first: How Cities Grow

This brings me back to my favorite academic paper I’ve read this year, The Neutral Criteria Myth. In a discussion about legislative redistricting, it points out that histories like Lacey’s show how city boundaries might look like simple lines on a map, but they are anything but neutral. These boundaries have long been used to shape communities, deciding who holds power and who gets resources.

Historically, these lines were often drawn with racial and economic bias. Redlining is a clear example, where minority neighborhoods were confined to underfunded areas. At the same time, wealthy, mostly white suburbs drew boundaries to separate themselves from urban centers, creating large gaps in wealth, schools, and public services. The truth is, there is no such thing as a neutral city boundary. These lines have always been about more than geography, they shape opportunity and segregation in ways that last for generations.

City lines affect property values, school funding, and even political representation. Local gerrymandering (redrawing district maps to favor one group) can tilt power and weaken others’ votes. Annexation decisions also play a role: cities often target areas that bring in tax revenue while avoiding neighborhoods that may be costly to serve.

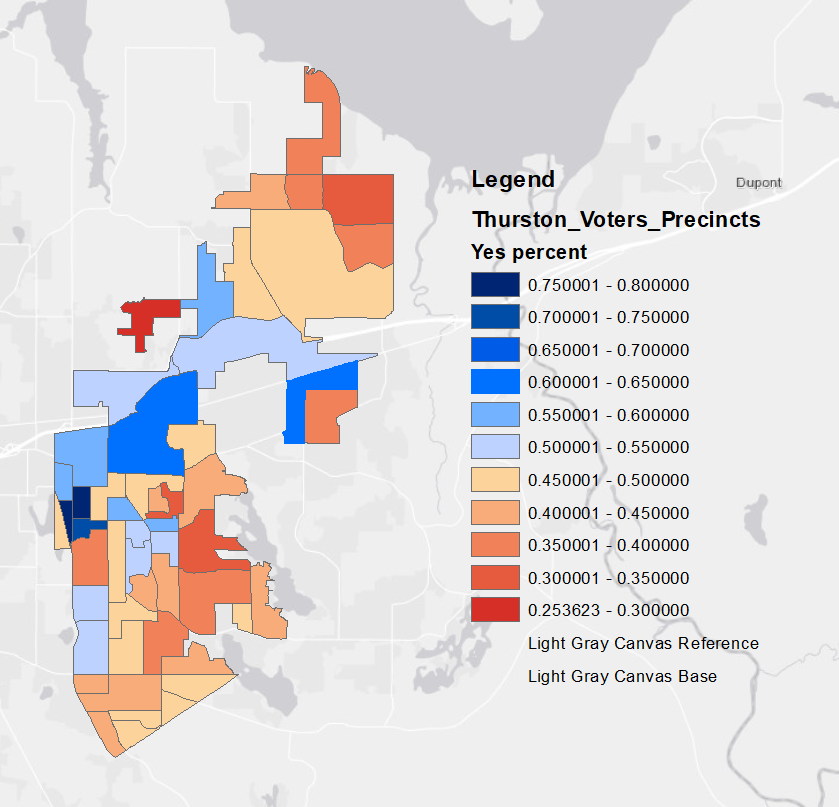

This is exactly the situation Lacey faces today. Decades after growth management laws placed the old Tanglewilde and Thompson Place neighborhoods in Lacey’s Urban Growth Area, the city is now looking back at the areas it skipped over. They have studied what annexing these unincorporated neighborhoods would mean. Their new financial analysis offers a clear answer: annexation would likely cost more than it brings in, at least in the near term. The study examined three growth scenarios, and in every case, the city would face a financial hit. Even after 20 years, the costs of police, fire, and utilities outweigh the tax revenue these areas would generate.

So, annexations have biases towards the needs of the current city residents. Systems like boundary review boards can help short-circuit these biases and bring more rational decision-making, but I think there is a broader model.

One idea I’ve been thinking about is to take city boundary decisions out of the hands of cities themselves. Currently, cities often push annexations for more tax revenue or strategic growth. But what if an independent board handled it instead, similar to the commissions used for legislative redistricting?

This board wouldn’t have a stake in politics or money. Its sole goal would be ensuring that services, water, sewer, police, fire, are delivered efficiently. It would focus on creating logical city limits that make sense for residents and future growth, not just for city budgets. The concept is simple: draw boundaries based on what works best for communities.

In many places, higher levels of government already step in to manage city boundaries rather than leaving decisions to individual cities. They do this because it can bring major public benefits, better planning, stronger services, and less wasteful competition between municipalities. Sometimes this happens through state or provincial laws. Other times, independent boards (like Boundary Review Commissions in the U.S. or Municipal Demarcation Boards in South Africa) take the lead. Their role is to look at the bigger picture: how to manage growth, avoid urban sprawl, and ensure communities are connected logically.

Why does this matter? When cities compete over territory for tax dollars, services suffer and local governments end up fighting instead of cooperating. Provincial or national intervention can fix that. In Canada, provinces sometimes merge or reorganize municipalities so services align and resources are shared fairly. In South Africa, national boards bring diverse communities together under one system, promoting equity and social cohesion.

The goal is simple: instead of a patchwork of self-interested annexations, create a more thoughtful, planned approach to city boundaries, one that serves people.