The streets were under a state of siege. They were gripped by a level of civic breakdown that feels ancient in its brutality.

A powerful media figure styled himself as a guardian of law and order. He spent months radicalizing the public against a perceived foreign threat. Through his writing and speeches, he cast social conflict as an invasion and dissent as subversion.

This campaign led to the formation of a heavily armed force that ignored the courts and civic institutions. In organized raids, its members rounded up hundreds of people they didn’t like. They beat them with clubs. They forced them at gunpoint out of town and banished them from the places where they lived and worked.

The air was thick with talk of Americanism versus treason. The local press framed these purges as a necessary cleansing of the community.

This wasn’t Minneapolis or Chicago in 2026. This was Hoquiam in 1912.

The events of the Grays Harbor County War started a political firestorm. It shattered local politics and created the framework for the immigration system we’re still fighting over today. What happened on the banks of the Hoquiam River wasn’t a weird one-off event. It was a prototype.

Albert Johnson was the central figure. He was a newspaper editor who later carried this model of vigilante justice to Congress. The workers he targeted were immigrants tied to the Industrial Workers of the World. Like the mob that stormed the Capitol on January 6, 2021, the Citizens’ Committee that terrorized the IWW was made up of local businessmen. These men believed they could restore order with ax handles and rifles. This conflict was a rehearsal for the nationalistic energy that became the Immigration Act of 1924. Our technology is different now, but the blueprint is the same. People exploit local unrest, turn economic stress into a cultural threat, and use that panic to justify national fear.

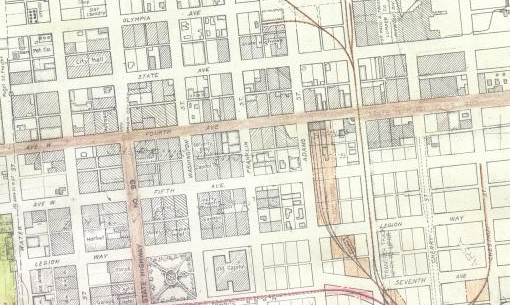

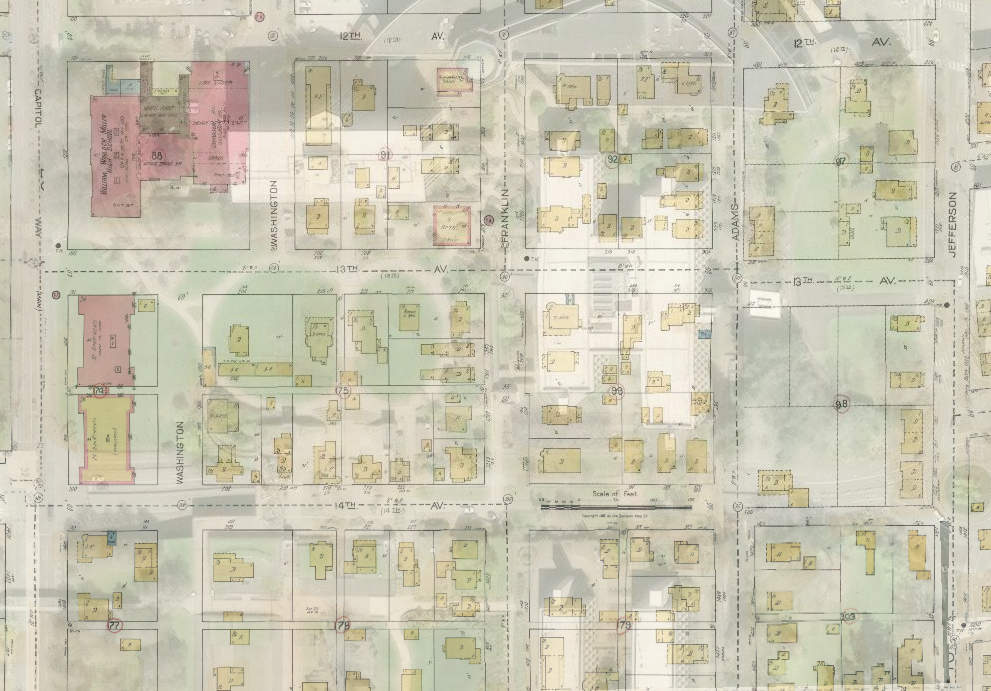

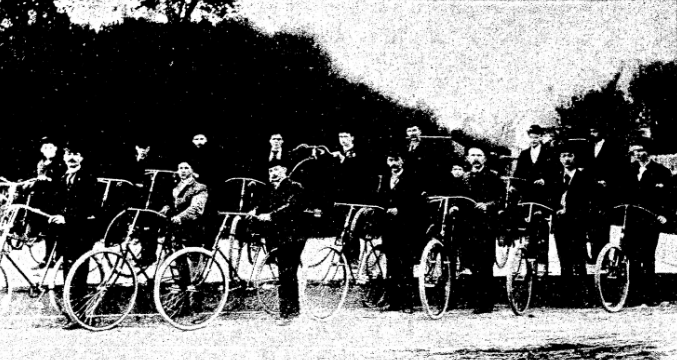

Grays Harbor was the lumber capital of the world. Its wealth came from the hard work of Finns, Greeks, and Slavs. These immigrant workers lived in dirty camps and worked ten-hour days in dangerous mills. In late 1911 and early 1912, the IWW organized them. They started with free speech fights and ended with a massive strike in March 1912. The mills stopped. The business elite panicked.

Johnson was the editor of The Daily Washingtonian. He became their main voice. He didn’t just write columns. He used his paper to help lead the Citizens’ Committee. This was a vigilante group made up of people who saw themselves as “respectable.” They ignored the police and did whatever they wanted. They raided union halls and beat strikers. By May 1912, they crushed the strike. Workers were loaded onto trains at gunpoint and told to never come back. Johnson told the public this wasn’t about wages. He said it was about protecting America from foreign anarchy.

That story became the foundation of his career. He was elected to Congress in November 1912. He brought another paper, the Home Defender, to D.C. to keep the fight going. Over the next decade, he turned the logic of Grays Harbor into federal law. Congress passed the Immigration Act of 1917, which added literacy tests. This was just the start.

By 1919, Johnson was the chairman of the House Committee on Immigration and Naturalization. He wanted his ideas to look official. He hired a eugenicist named Harry Laughlin to be his expert. The results were laws that narrowed who was allowed to be American. In 1921, he wrote the Emergency Quota Act. In 1924, the Johnson-Reed Act finished the job. It used the 1890 census to decide who could enter. This was a trick to exclude the same Southern and Eastern Europeans Johnson fought in Washington. When President Coolidge signed it, Johnson called it a second Declaration of Independence.

He turned mob violence into a government machine. Things like deportation and visas weren’t acts of a crowd anymore. They were part of a permanent system.

Alternative History of Hoquiam

But I’m not writing today to just tell you what happened in Hoquiam was inevitable. Right now, we’re trying to find a way out. So, let’s imagine a world where Johnson didn’t succeed.

But what if this didn’t happen? It’s useful to look at how history could have gone differently. We’ve seen that history isn’t always a straight line. There’s a version of this where the “Red Coast” didn’t just resist but built a bridge between different groups. Imagine if the 1912 strike ended with a coalition of workers and farmers. In this version, the local middle class is disgusted by the violence. They decide that you can’t have law and order if you’re breaking the law to get it. Johnson’s paper is sued for libel. He loses his money and his reputation before he ever gets to D.C.

The Washington State Grange helped make this possible. They were a powerful group of farmers who cared about the democratic process. They hated the vigilantism of the Citizens’ Committee. They saw the deportations as a threat to everyone’s civil liberties. The Grange condemned the business elite. They put their support behind local leaders who stood against the violence. This gave the middle class the cover they needed to speak up. It broke the power of the anti-labor group and made room for a new Labor Defense League.

In this timeline, Stanton Warburton, a progressive Republican, wins the 1912 election instead of Johnson. He beats him by speaking out against the ax handle tactics. Because Warburton keeps his seat, the path to the 1924 Act is severed. Instead of racist quotas, we get the 1928 Integration Act. It creates a federal office to help new workers. By 1930, 18% of the population is foreign born. These people become a huge group of customers that helps the economy stay stable during the Depression. American identity becomes about what you contribute rather than where your parents were from.

The labor movement wins by changing what it means to be American. They argue that including people is the best way to stop exploitation. The Labor Defense League teaches English and civics while they organize. They say an immigrant with a union card is a better American than a man with a club.

Without Johnson, eugenics would never have become a part of our policy. The leaders of the immigration committee are progressives who care about the economy, not “purity.” This focus on solidarity changes everything. Unions and farmers work together. Farm owners in the fruit regions agree to fair wages and housing in exchange for a stable workforce. They create a direct path to citizenship.

If that had happened, our politics today would be different. We wouldn’t be obsessed with demographics or cultural panic. We’d talk about economic solidarity instead. We wouldn’t hear much about “replacement” or “dilution.” We’d focus on building unions and protecting workers. This would stop the race to the bottom that makes people hate immigration.

Our experts would change too. We wouldn’t listen to people who scream about border crises. We’d listen to people who study how to help newcomers join the community. Success would be measured by how fast people pay taxes and join the workforce.

Johnson’s power came from turning local fights into a national panic. We still see this. A fight in a city or a border dispute becomes an existential crisis. The lesson of this alternate history is that local resistance matters. If Hoquiam had said no to Johnson in 1912, we might have a more open democracy today.

The 1924 Act is still with us because it made immigration a matter of crime and race. Before Johnson, “illegal aliens” weren’t really a thing in our laws. He built the world of border patrols and caps. Even after the overtly racist parts were removed in 1965, the structure stayed. Johnson didn’t just win a fight in a small town. He changed the whole conversation. He made us ask if people should be here at all instead of asking how to welcome them. That choice still has us stuck today.

The Current Counterfactual

We can see the emotional reality of this counterfactual in modern Pacific County. It sits right next to Grays Harbor. In 2017, the area was shaken when ICE agents detained Mario Rodriguez at the post office in Long Beach. Mario wasn’t a stranger. He’d lived on the peninsula for twelve years. He worked as a bilingual teaching aide in the local schools. He was a neighbor, a volunteer, and a friend. When he was taken, the reaction from the local white community was not what you might expect. Many of these people had voted for the very policies that led to his arrest, but they weren’t happy. They were shocked.

Even the local police chief, Flint Wright, was rattled. He had supported a tougher border, but he spoke up for Mario. He called him a pro-law enforcement guy. He said anyone would want him as a neighbor. This reaction shows that when abstract talk about “illegal aliens” meets a real human being, the old logic falls apart. The people of Pacific County didn’t see an invader. They saw a hole left in their neighborhood. They formed a support group that eventually became a nonprofit. They fought for their neighbor.

This local pushback is today’s proof that Johnson’s vision was never inevitable. It shows that even in the conservative timber and fishing towns of Southwest Washington, people can choose their neighbors over a club. The ghost of 1924 is still in the machine, but stories like Mario’s remind us that we can choose a different path. We don’t have to live in the reality Albert Johnson built. We’ve seen a glimpse of something else. It’s much closer than we think.