|

| Missing Middle from AIA Austin |

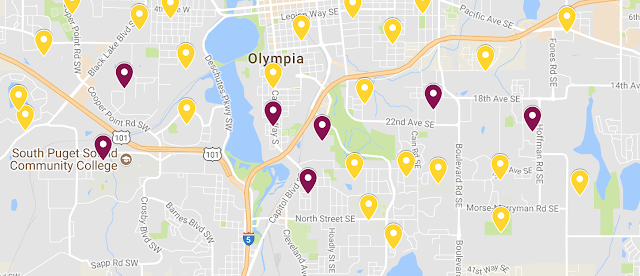

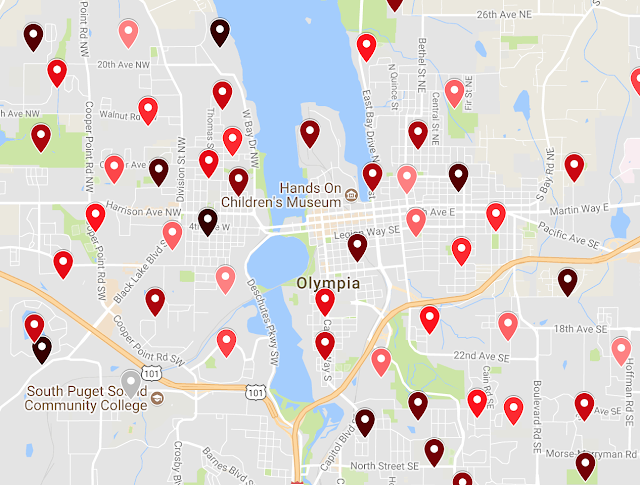

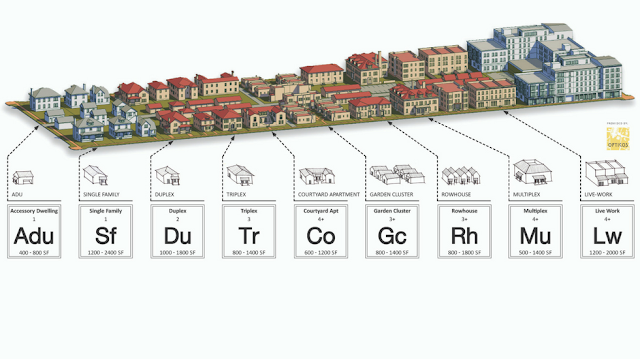

Right now the Olympia planning commission is considering a list of recommendations about the so-called Missing Middle. These recommendations would hopefully increase density in Olympia’s least dense neighborhoods by allowing duplexes, townhomes, courtyard apartments and ADUs in the mostly the upper elevation swaths of single-family homes neighborhoods.

As you would expect, there are a bunch of people who are not fans of this idea. And as you might expect, they belong to existing neighborhood organizations in well established (but I would argue not traditional) residential neighborhoods. As Whitney Bowerman argued in this excellent email she sent to the planning commission, these organizations represent mostly older homeowners who want to preserve the low-density character of their neighborhoods.

This testimony to the planning commission I think almost perfectly encompasses this attitude.

First off, she makes a point that we shouldn’t follow the example of Seattle. Implying that by increasing density you don’t do much to decrease housing costs. The fact is that rents and housing costs have started to decline in Seattle, mostly because of all those cranes on the skyline are starting to make a dent in demand.

Renters are not bad, I’m a renter

About two minutes into her testimony, she starts to get into a caricature of homeownership. “For generations, working people have dreamed of owning a house,” she said. Specifically a house, and in her mind, a detached single family home. Which is also a specific type of home that hasn’t been historically accessible to many people or even now.

“It is not just a financial investment, it is an emotional investment and a social investment as well,” she said. Apparently, when you own a home, your emotions should matter more and your memories are deeper and richer.

“Outside those walls and over the fences, they (homeowners) create social networks,” she said. “Perhaps not in the days of old when someone was home and could build social capital in the neighborhood, but people do participate in Nextdoor, attend annual meetings… they are literally invested in their neighborhoods.”

This is all a slam on the nature of renting a home. Personally, I’ve done both. I’ve rented in almost every quadrant of Olympia and owned two homes in East Olympia. Currently, I rent an apartment in Southeast Olympia and hope one day to own again, but not a single family detached home. My goal is a townhouse with as little yard as possible.

But this belies the philosophy behind this anti-density testimony. The neighbor I had that called me a piece of shit while I was outside with my toddler owned his home. He still owned it when the police arrested him for waving a gun at his wife. I’m sure he had memories in my neighborhood, but they weren’t more meaningful because he paid a mortgage.

I’ve also had a series of neighbors that have quickly moved in from out of state, bought a home and relatively quickly moved out without making a dent in my community. They were not literally invested in anything and their presence, while pleasant, did not have a deeper impact on the neighborhood.

It isn’t about renters vs. homeowners, it’s about density and affordability

I agree the research indicates that homeownership by-in-large means better things for a community.

The testimony is also moving the ball from a debate on increasing density in Olympia’s low-density neighborhoods to a debate over the value of homeowners vs. renters. At least in the examples of townhomes and possibly courtyard apartments, the Missing Middle will be the only actual path to homeownership that some people can ever use. And, the option of duplexes and ADUs will possibly allow some folks, who would like to set down permanent roots in a neighborhood, stay in a neighborhood.

Imagine for a moment a single mother who got a late start on retirement. She has an addition in her small home that she can easily transition into an ADU if it was allowed by the city. That would keep her in her home past retirement.

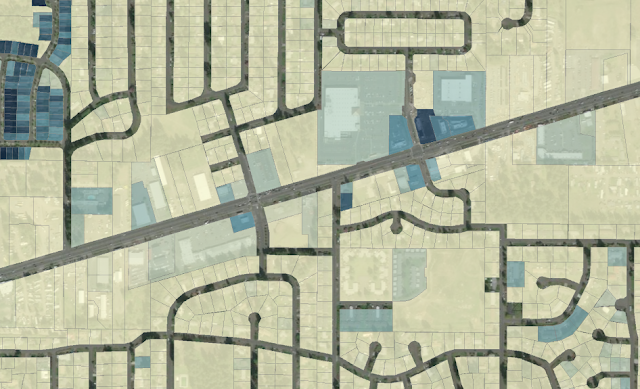

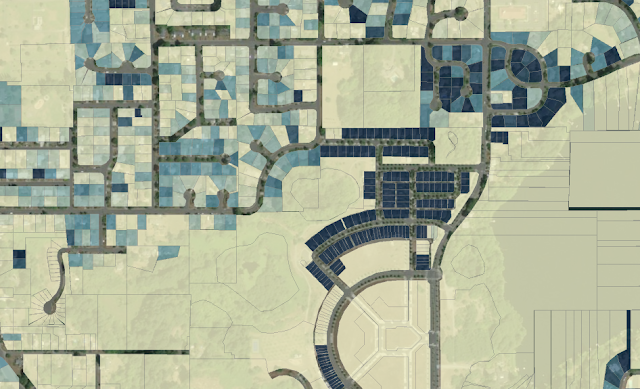

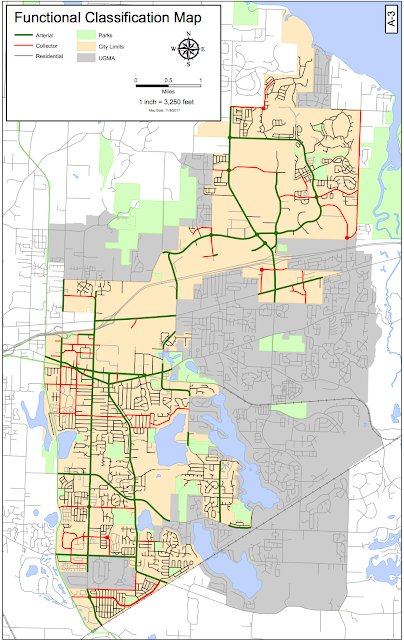

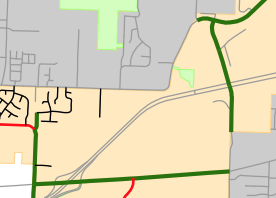

Currently, a lot of neighborhoods in Olympia fail the test of liveability in two major ways. They are too low density to really be considered walkable. Even if a small neighborhood center like Wildwood did want to located inside some of these neighborhoods, it wouldn’t survive because single-family neighborhoods simply aren’t dense enough.

Also, we fail in terms of variety of housing types, especially in the car-dependent SE neighborhoods. A good neighborhood ensures that multiple generations of the same family can live in the area, that people from a variety of backgrounds can come together. Large swaths of single-family homes, while protecting the nature of a neighborhood, does not promote diversity.