1. Holmes got smoked.

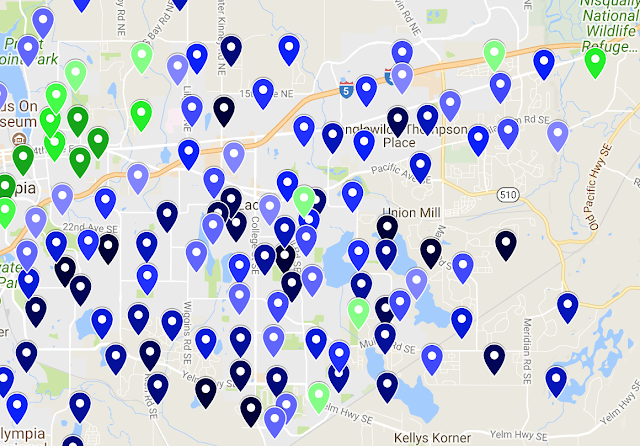

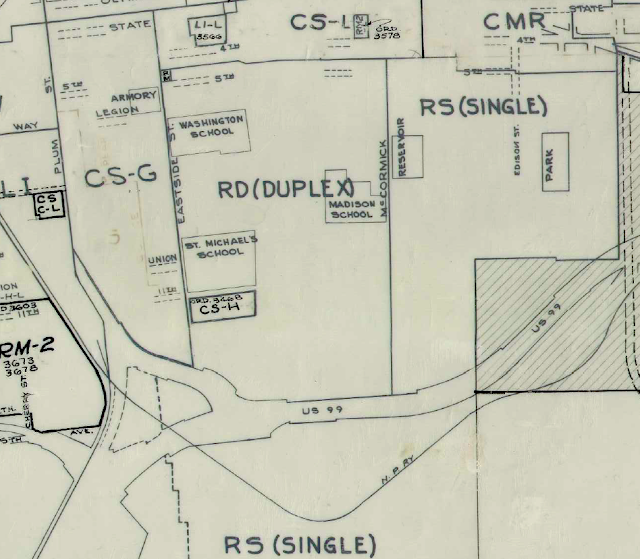

This doesn’t take much explaining, his overall percentage (32 percent) of the vote being what it is, seeing Stuart Holmes mapped out doesn’t give you much more insight.

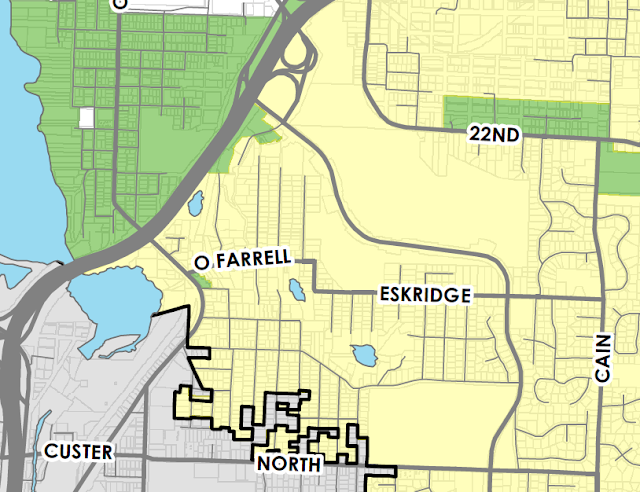

At the very least, he follows the same north to south, liberal to conservative pattern that we usually see in Thurston County. Conservatives work from south to north, liberals the other way around. But is the independent label magic gone? I mean, I can’t expect he did much better as an Independent than he would have done as a Republican.

2. Where did these Minjares precincts come from?

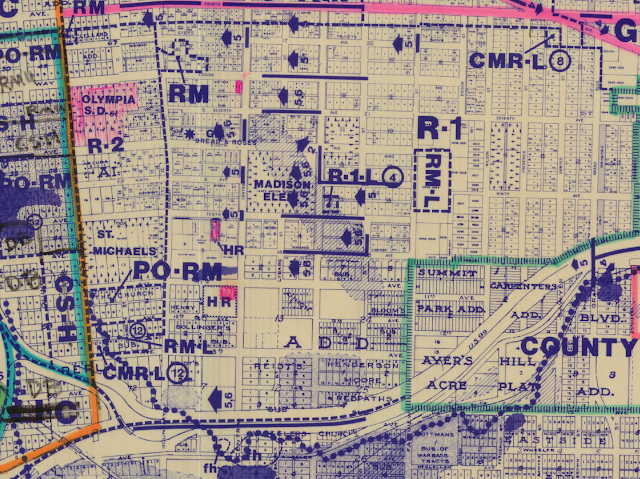

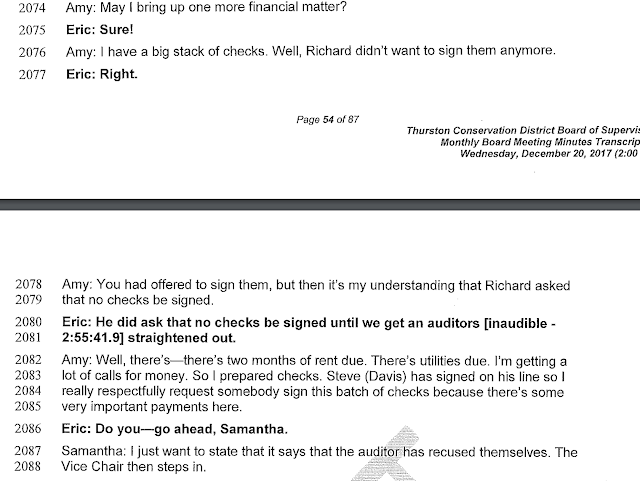

One thing you can say about the Hall/Holmes race for auditor, is that it followed the typical south to north, conservative to liberal track of Thurston County. The Tunheim (as the conservative) and Minjares (as the liberal) results follow the same track.

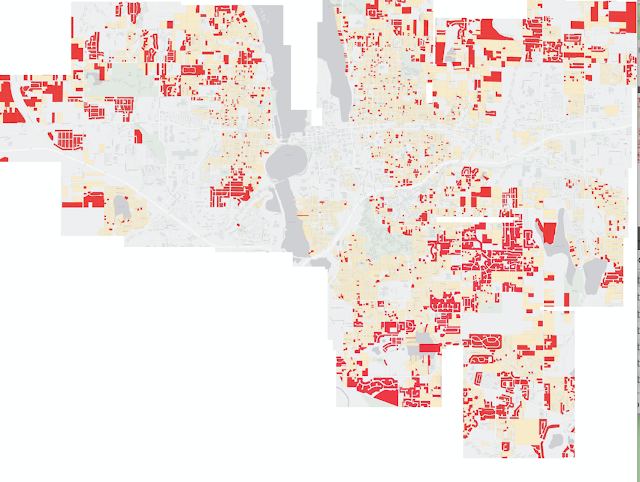

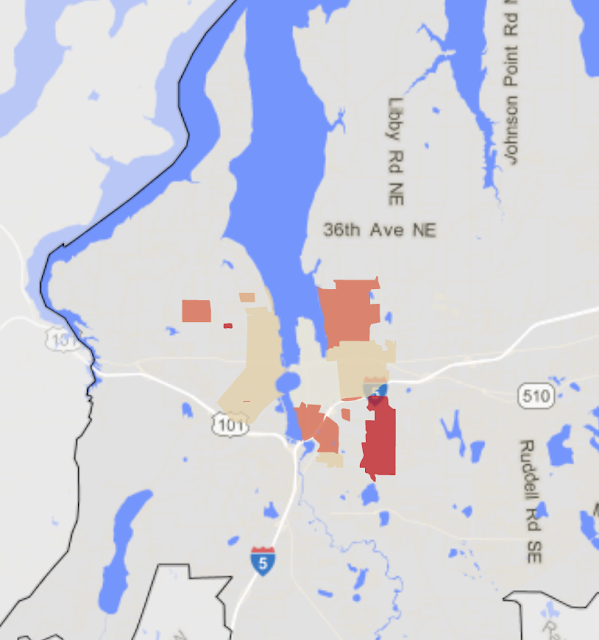

But, Minjares won a handful of precincts both in the far southeast part of the county and out in Lacey. Alternatively, Tunheim won a lot of precincts inside Olympia that I would have assumed stayed on the liberal side of things.

There are different dynamics in play in this election than we’ve seen in local elections recently. Things like diversion programs and how prosecutors choose to advance cases aren’t your typical county-level land use questions we deal with. So, I’m wondering if we’re going to see a new map emerge.

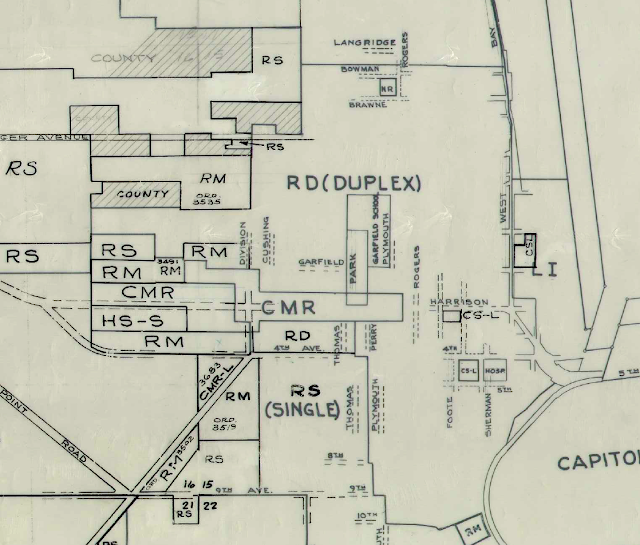

3. Bud Blake lost in no small part because he lost ground in rural precincts

Bud Blake lost this primary even though he got the most number of votes. He finished with less than 40 percent of the vote, while the rest was largely split between two Democrats. You can say he lost because he wasn’t able to get distance from two Democratic challengers and as an incumbent, he trailed the 50 percent mark by a large margin.

But, I say the biggest reason he lost is that he lost to himself four years ago.

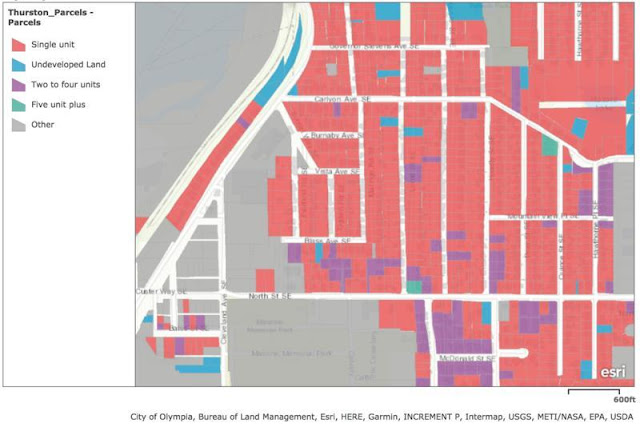

Most surprising in this map was how poorly Blake did against his own results in the primary four years ago. Sure, he lost votes in Olympia (not so many in the water facing districts, more in the newer neighborhoods). But he lost a lot of votes in the rural precincts, especially in a handful around Rochester. In some of these precincts, he ran twenty percent better four years ago.

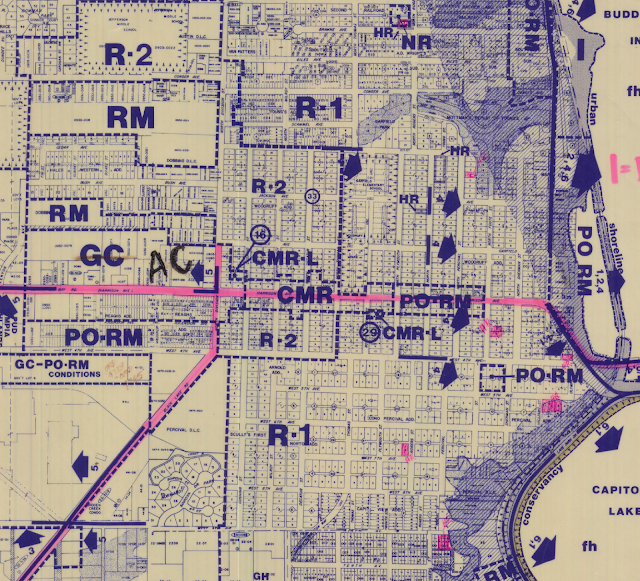

4. What kind of voters are Denton voters?

Being able to predict what will happen in a few months in the general election depends on how the voters for a failed primary candidate decide to act. In this case, the voters who chose Melissa Denton will decide whether to support Blake or Menser. And where they decide to go depends on how they saw Denton. If they made the choice for her because they saw her as more moderate than Mesner, then Blake might actually pick up some of those votes. Even though I’ve heard people say she’s the more moderate choice, I’m not sure.

The most Denton precincts in this map seem to be a straight line from the outside of the Olympia westside into Tumwater, which gives some credibility to her being a moderate candidate or at least a moderate candidate from the voters’ point of view. But, she also won College, which is the most liberal precinct in the county. So, who knows?

5. Can Blake make it back?

This is a non-map segment, mostly just an explanation of how difficult I think it will be for Bud Blake to win in November.

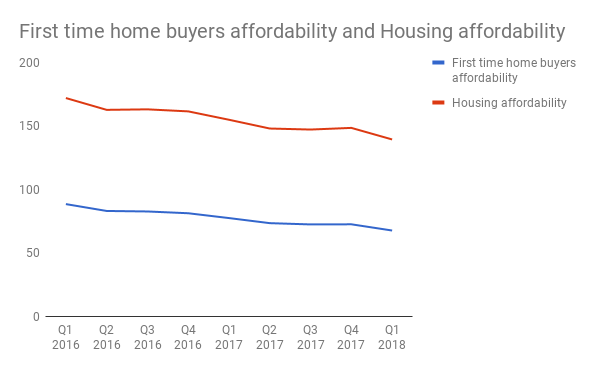

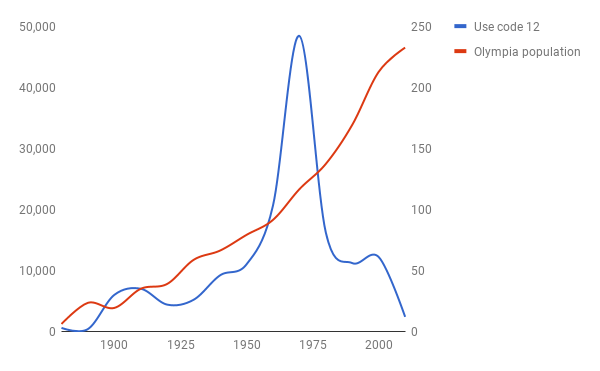

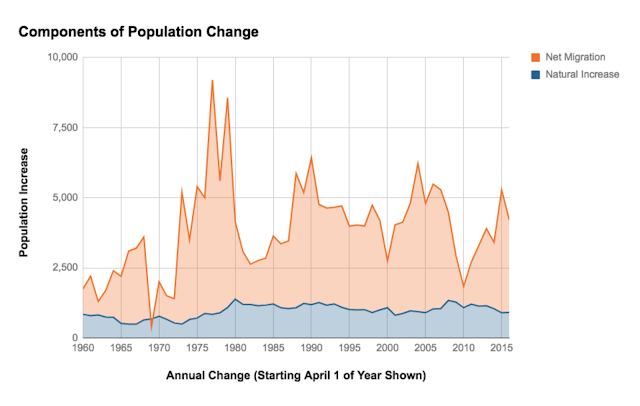

So, we start with three things we know: Bud Blake got 35 percent in this primary, 48 percent in the 2014 primary and won the general in 2014 with about 55 percent of the vote. Because primaries for county commission are run in one of three districts and general elections are county-wide, you can assume that Blake found an increase of support in the other two districts in 2014. But that is not what happened.

If you pull apart the 2014 general results, he did slightly better in the third district (his home district) in the general with 55 percent than he did in the other two (54 percent). So, it isn’t like there is a new, untapped well of support out in those areas that haven’t weighed in yet. As it stands, he’ll have a harder time of it when the geography expands, if only slightly.

And, this year, he’s starting well further behind than he did in 2014. If you take the returns from the 2014 primary and general and extrapolate primary returns for the other two districts (like on the back of a napkin for example), Blake only finishes at around 45 percent in a 2018 general. But, that is only we consider his comeback in 2014 as the limit of his ability to climb.

Which, since we’re likely looking at a “blue wave” election this time around as opposed certainly not a blue wave in 2014, that ceiling for Blake might well be a hard one.