It seems like we might be in the habit of doing this every decade or so in Washington State, bringing back the legislature to make sure Boeing doesn’t leave Puget Sound high and dry. The risk of losing Boeing to some other state is an interesting case of regional tension, especially in how Colin Woodard describes regions in American Nations.

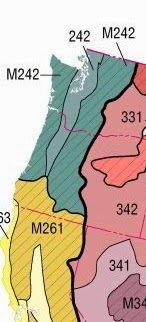

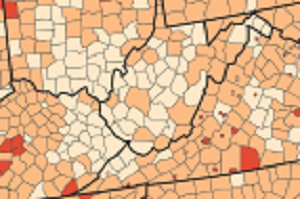

Right now, at least on their commercial airline business, Boeing is company with deep Left Coast roots. But, in recent years, Boeing merged with another aerospace company from Great Appalachia (McDonnell Douglas). Since then, they have begun using the political and economic culture of the Deep South to gain concessions from their Left Coast home.

This contrast between their Left Coast origin and Deep South destiny is interesting.

On the surface, the Left Coast (home of Portlandia, hippies and Starbucks) seems like the perfect anti-corporate foil to the open-for-business Deep South. But, as Woodard points out (and the Boeing legislative package illustrates) there is a deep vein of pro-business sentiment in the Left Coast.

The Left Coast was founded in part by New England capitalists, who built the region on large timber empires. This timber baron sentiment led directly to the founding of companies like Boeing. It was also based on a close understanding with civic leaders to do what was needed to keep people at work and business growing.

The other founding group along the Left Coast is the Great Appalachians. They could also be described as pro-business, but as expressed in the founding of Oregon, not exactly pro-big business. So, while companies like Boeing stayed home grown they were happy enough to stay out of their way.

That particular brand of pro-business from the Appalachians of the Left Coast might be turning against Boeing in their post McDonnell Douglas, Chicago headquarters period. The recent legislative session in Olympia was cast in a “David vs. Goliath” light by at least one Republican lawmaker:

“Boeing is vital to our state’s economy,” said Holmquist Newbry, R-Moses

Lake. “The thousands of jobs produced by the 777X program will have a

positive economic ripple effect throughout our state. The Legislature,

however, is being asked to provide special incentives for Boeing. My

response is this: If these policies are good for Boeing, then they

should be good for all of our employers. Unfortunately, expanding these

incentives to help other, smaller businesses survive and thrive is not

even on the table right now.”

…

“If a Goliath multi-billion dollar company and its team of lawyers have

difficulty navigating our state’s permitting process, and need the

certainty of a four-week permitting timeline, what chance do our

Mom-and-Pop businesses have in navigating the same permitting process?

If it’s good for Goliath, it’s good for David.”

But, along with these various pro-business strains in the region, the Left Coast also developed a strong sense of civic mission (at least in urban areas) and environmental protection.

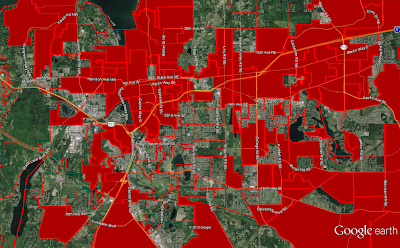

So, where in the country can Boeing get a better deal to build planes than its home region? Well, the Deep South. Remember, if Boeing does end up expanding more in the Deep South, it will be near Charleston, SC (from Business Week):

Beginning from its Charleston beachhead, the Deep South spread apartheid and authoritarianism across the Southern lowlands, eventually encompassing most of South Carolina, Georgia, Alabama, Mississippi, Florida and Louisiana; western Tennessee; and the southeastern parts of North Carolina, Arkansas and Texas. With its territorial ambitions in Latin America frustrated, it dragged the U.S. into a horrific war in the 1860s in order to form its own nation state, backed by reluctant allies in Tidewater and some corners of Appalachia.

After successfully resisting a Yankee-led occupation, it became the center of the states-rights movement and racial segregation, as well as labor and environmental deregulation. It

is also the wellspring of African-American culture in America

and, 40 years after it was forced to allow blacks to vote, it

remains politically polarized on racial grounds.

For all our pro-business culture (we built Microsoft, Weyerhauser and Boeing), we Left Coasters also have a strong sense of unionism and environmentalism. This is the New England sense of community values expressing themselves in our culture. We also have an Appalachian sense of fair play that is questioning special deals for few large companies.

So, where is a company supposed to go to get away from all Left Coastiness? Well, Charleston, the birthplace of the Deep South!