We’ve all heard President Donald Trump call the press “the enemy of the people.” Over the course of his terms, he repeatedly attacked news organizations as “fake,” “corrupt,” and even suggested some were engaged in illegal activity.

Beyond insults, he openly questioned the constitutional protections that shield journalists, including the landmark New York Times v. Sullivan precedent, and proposed “opening up our libel laws” so politicians could sue and “win lots of money.”

His rhetoric and actions exemplify a long-standing tension in American democracy: the fragile balance between government power and press freedom. Yet this struggle is far from new, and it is not new here at home. Nearly a century ago, in Thurston County, local politics intersected with criminal libel laws in a way that foreshadows today’s conflicts.

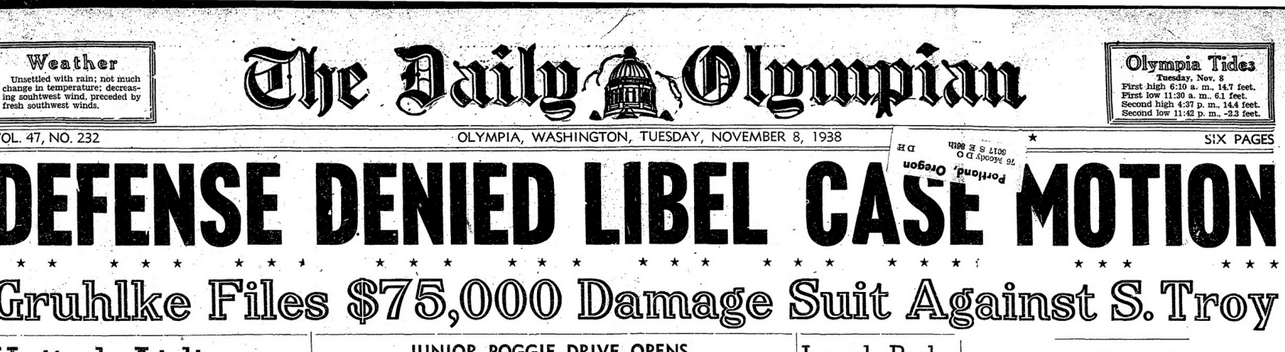

The story begins in November 1938, when Thurston County Prosecuting Attorney Smith Troy filed criminal charges against three men: Ray Gruhlke, Lester Main, and George Johnson. He accused the defendants of distributing handbills that allegedly defamed Troy and his brother Harold, who was an assistant county prosecutor. The charges contended that the statements were malicious and intended to expose the Troys to “hatred, contempt, ridicule, and obloquy,” depriving them of public confidence, consistent with the criminal libel statutes of the time.

Almost immediately, questions arose about the integrity and motives of the public officials involved. The circumstances of the arrests suggested potential overreach, and critics argued that the case may have been politically motivated to protect the interests of Smith Troy while undermining his opponents. Affidavits from law enforcement contained conflicting accounts of the arrests, raising doubts about the accuracy and impartiality of the official record. The court initially denied motions to appoint independent attorneys to investigate the charges, further highlighting the potential for bias. The case only began to take a more credible direction once a Special Deputy Prosecuting Attorney, Harry Ellsworth Foster, was appointed to replace Smith Troy, whose personal involvement as the alleged victim created an obvious conflict of interest.

Over the next several months, the Special Prosecutor’s investigation revealed that the alleged libel stemmed largely from confusion over incomplete court records. The handbills pointed to cases that the Troys were apparently prosecuting improperly, but the cases referenced in the pamphlets had been transferred, and the inconsistencies were clerical rather than malicious.

The defendants admitted their errors, tendered apologies, and Troy accepted them. By May 27, 1939, the court dismissed the case, noting that the controversy had prompted reforms to ensure future records were clearer and less prone to misinterpretation.

The Thurston County case cannot be fully understood without situating it within the broader legal context. Smith Troy would not have been able to pursue charges without statutes defining libel broadly as any malicious publication exposing living or deceased persons to hatred or contempt, or injuring any person in business or occupation. A person could be prosecuted even if the statements were true, unless published with “good motives” and “for justifiable ends.”

By the 1930s, criminal libel prosecutions had become rare, yet the statutes remained on the books through 2009, offering public officials like Troy a tool—however rarely used, to protect reputations through criminal law.

The law’s overreach and constitutional vulnerabilities became clear in 2008, when the Washington Court of Appeals struck down the criminal libel statute as facially unconstitutional. The court held that it violated the First Amendment because it punished false statements without requiring proof of actual malice and, paradoxically, could punish true statements lacking “good motives.” The legislature formally repealed the law in 2009. Modern statutes surrounding protection orders have partially revived criminalized libel in limited circumstances, primarily to address harassment and repeated false statements made with malice.

The Smith Troy case illustrates how criminal libel statutes historically empowered officials to suppress criticism, a temptation not lost on modern politicians. Trump’s attacks on the press echo the same impulse: using legal threats, regulatory power, and public shaming to undermine journalists and chill reporting. Unlike Thurston County in 1938, Trump operates on a national stage, with the ability to influence federal agencies, control access to government events, and challenge the judiciary’s interpretation of defamation law.

Yet the comparison also highlights both the fragility and resilience of press freedom. In Thurston County, the appointment of an unbiased Special Prosecutor and the eventual dismissal showed that legal checks, due process, and transparency can constrain abuses of power. Today, protections like New York Times v. Sullivan perform a similar role, ensuring that even powerful political actors cannot easily weaponize libel law against the press. Without these safeguards, the line between legitimate critique and suppression of dissent blurs, leaving citizens less informed and democracy weaker.

The trajectory from Smith Troy to Trump underscores that the press is both a target and a guardian in any democracy. Laws may criminalize speech, but misuse or selective enforcement erodes trust in both institutions and government itself. Meanwhile, as local news declines and national outlets consolidate, the onus falls more heavily on government to act transparently. A free press alone cannot ensure accountability; officials must make accurate information accessible, clear, and timely, or risk leaving the public in the dark.

History reminds us that power will always test the boundaries of scrutiny. The Thurston County libel case offers a microcosmic lesson: fair process, independent oversight, and transparent government are essential to maintaining the balance between authority and the public’s right to know. Today, as political leaders attack media and propose changes to defamation law, the stakes have moved from local to national. The core principle remains unchanged: the press must remain free to speak, investigate, and hold power accountable, and government must meet its own obligation to be transparent in a media environment that can no longer do it alone.

Leave a Reply