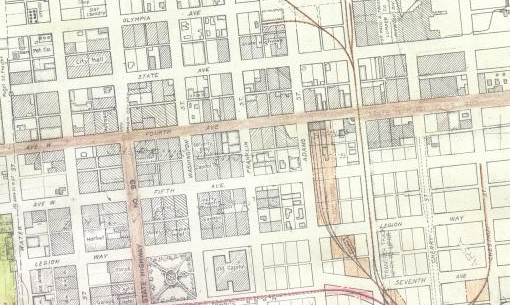

The layout of downtown Olympia is burned into my brain. It just seems inherent to the space that coming down from the Upper East Side, both State and 4th are one-way. Especially coming from my neighborhood, this doesn’t always make 4th and State the fastest way across town. But it does feel like it’s always been this way, that when we created this part of town, the original layout was two paired one-way streets.

But that’s not actually true. Before the late 40s, downtown was just a normal grid. You could go both ways on every street.

The switch to one-way streets wasn’t some long-planned city project either. It was an accident caused by a massive earthquake in 1949. What started as a quick fix to get around piles of fallen bricks turned into a permanent setup. Then the state highway department saw an opening to turn our local streets into a highway for commuters, and they took it. It’s a classic case of prioritizing fast cars over a walkable neighborhood.

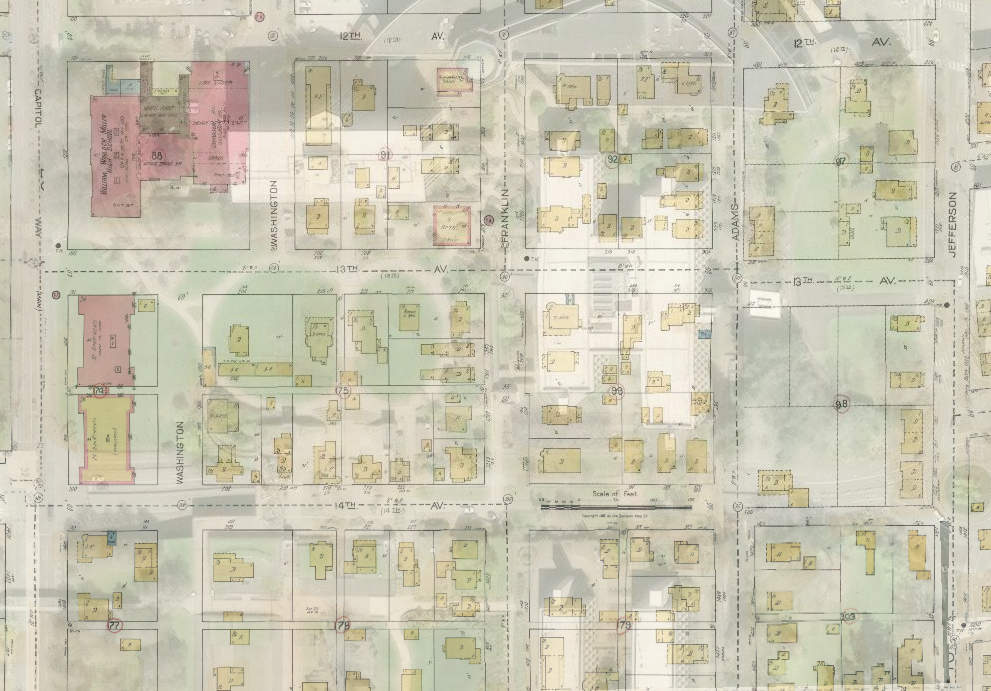

Before 1949, Olympia’s downtown felt a lot tighter and more connected. We didn’t have all these massive parking lots everywhere. Instead, it was just row after row of actual buildings. This was also when the residential neighborhoods surrounding downtown were interconnected using similar grid patterns, before growth had grown beyond Division on the west and Boulevard on the east.

When a street goes both ways, twice as many people see a storefront. You aren’t “eclipsed” by the direction of traffic. But after WWII, engineers became obsessed with “throughput.” They stopped thinking about downtown as a place to be and started seeing it as a hurdle to drive through. They wanted to move the tides of cars as fast as possible. The old two-way grid was standing in their way, but it took a disaster to finally break it.

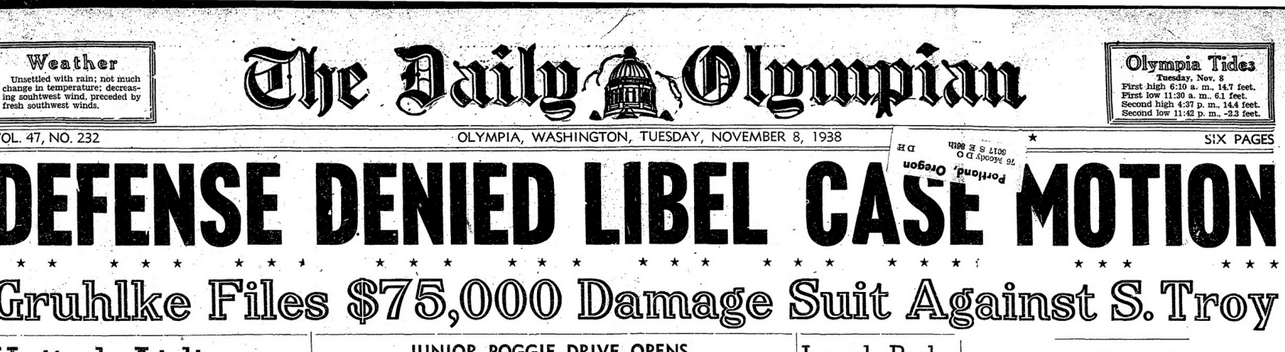

The real turning point happened on April 13, 1949. It was just before noon when a 7.1 magnitude earthquake hit. It was the biggest one the region had seen all century. Two people died, and the damage was immense. Eleven buildings were so damaged that they had to be boarded up immediately.

4th Avenue and State Street were a mess. To keep things moving while crews cleaned up the rubble, the city made a quick call: make them one-way. It was supposed to be a temporary fix to manage the chaos. But the streets never went back to the way they were. The earthquake gave engineers the perfect excuse to push a one-way vision that had been bubbling under the surface for years.

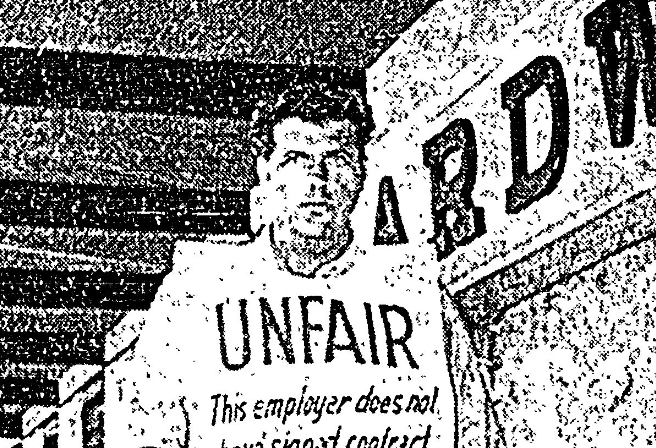

By late October, downtown business owners were joining forces to ask for a return to the pre-April alignment downtown. “Promises were made to return to two-way traffic as soon as the emergency was relieved,” said a downtown druggist and head of a business committee.

This is where the State Highway Department really left its mark. As the city debated whether to keep the temporary measure through the fall of 1949, the state didn’t just suggest keeping the one-way streets; they basically mandated it. They decided to fold 4th and State into the state highway system. 4th Avenue became the southbound lanes for the Pacific Highway, and State Avenue took the northbound traffic.

The legislature had passed a law the year before, allowing the Highway Department to take a heavier hand in ensuring state highways efficiently passed traffic. To that end, the highway department studied the issue of now one-way streets in Olympia and gave the city government two options: stay with one-way or lose all the parking along 4th and State.

By doing this, the state prioritized regional travel over the people actually living in Olympia. The main goal was throughput, moving people from the suburbs to their jobs or across the state as fast as possible. Our downtown streets weren’t local roads anymore. They were effectively a highway split in half. Once that highway designation was set in stone, there was no going back. The state had its high-speed corridor, and the city was stuck with the noise and the speed.

Business leaders talked about suing, saying the state was taking too heavy a hand. But no lawsuit followed, and downtown settled into its current pattern. Just less than 10 years later, Interstate 5 bypassed downtown Olympia, but one-way streets stayed.

We’re still paying for that 1949 decision today. On paper, one-way streets move cars fast, but they make life harder for everyone else. Research shows that child pedestrians are 2.5 times more likely to get hurt on one-way streets. It makes sense if you think about it. Drivers get into a highway mindset and stop looking for people.

Looking back, the 1949 earthquake broke the way Olympia functions. We traded a walkable, easy-to-navigate downtown for a system that treats downtown like a bypass. This isn’t even getting into the number of buildings that were torn down in the last 75 years to make way for parking.

I focus a lot of attention on downtown Olympia in this discussion. But it is worth pointing out that most of the mileage for the one-way streets in Olympia goes through formally residential neighborhoods. The city has slowly changed how the blocks are treated around the one-way paired throughfairs, but to me, even if we build denser, mixed-use neighborhoods up the Eastside hill, slower, more people-oriented traffic orientation makes sense as well.

Today, plenty of cities are realizing this was a mistake. They’re converting one-way streets back to two-way streets to lower crime, help local businesses, and stop the constant speeding. It makes you wonder what Olympia would look like if we had just cleared the 1949 debris and stayed the course with our original grid. We might have had a downtown that feels more like a community and less like a race track.