The Red Coast is a rare book of Pacific Northwest history that unpacks a vital era. The labor, free speech, and political wars in the first third of the 20th century is an often misunderstood and glossed-over part of our heritage. Written by three authors, including two St. Martins Saints (I guess), the episodic nature of the book makes it interestingly readable.

This book goes straight onto my shelf of classics of Pacific Northwest history. My criteria are generally works that are based on original research and primary sources, but also take a new perspective. Red Coast does both of these in spades.

Other works I put on that shelf include Confederacy of Ambition, by William Lang, and the three statewide histories by Robert Ficken. Red Coast gives a clear view of a unique period in our history. Despite the well-known incidents, such as the Centralia Massacre, Red Coast ties these lowlights into a consistent narrative that redefines our understanding of regional history through the Depression.

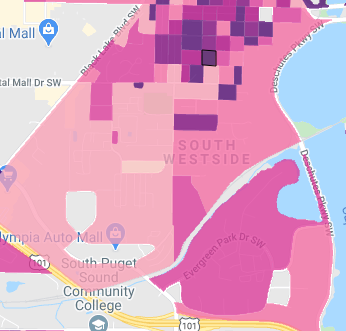

My primary insight, though, is on the second part of the subtitle of the book: Anti-Radicalism in the early 20th century. Or, what seems to be now the conservative re-radicalization of Southwest Washington.

Throughout my life, Southwest Washington has always been a stable, union-friendly Democratic bastion. In fact, this has been true since the re-alignment of politics in Washington after the 1932 election. Before the Roosevelt wave election in 1932, Washington was a Republican supermajority state. Democrats in 1932 swept the table and reestablished a new balance of power. Even after the parties again realigned in the late 1980s (King County voted for Reagan twice!), Southwest Washington Democrats held onto a seemingly genetic stranglehold on legislative and countywide seats in Grays Harbor, Pacific, and other Southwest communities.

Obviously, since the 1980s it became plenty obvious to point out a Democrat from South Bend was not the same kind of Democrat from South Seattle. But the big Democratic Party tent was big enough to keep the Coastal Caucus happy and on the team.

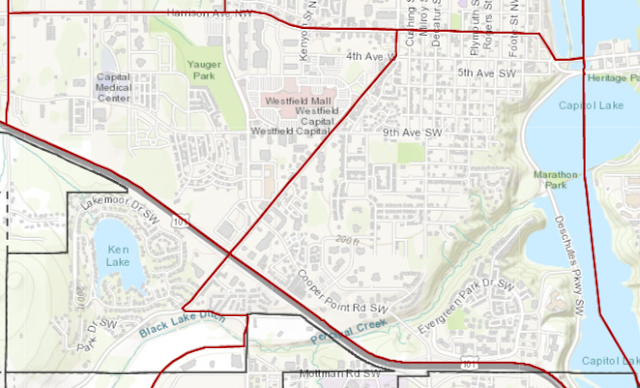

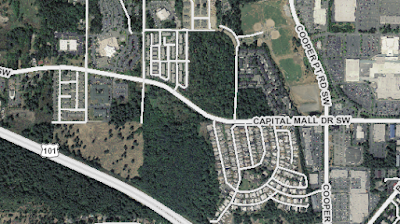

The taste of the coastal voters seemed to change in recent years with less than stellar returns for top ticket Democrats. The election of Rep. Jim Walsh and how well Trump did the same year in Southwest Washington indicates that in a decade or so we’ll be talking about how the region re-aligned, yet again.

After reading Red Coast, I’m not sure if this is a re-alignment or the end of an 80-year truce or a tapping into of a strong political tradition in the region. The echos between current conservative politics and the chapter on Rep. Albert Johnson are strong. Rep. Johnson served in the 3rd Congressional District for almost two decades and was a direct product of the anti-radical movement in Southwest Washington described in The Red Coast. While anti-radicalism is the second fiddle nemesis in The Red Coast, it seems to be the more lasting phenomenon worth studying. I don’t want to spoil the book, but the Wobblies did not win.

Johnson’s primary legacy was anti-immigrant politics and actual anti-immigrant legislation. I need to do more work on this, but there seems to be a direct tie-in from Johnson’s political work to the specific Oregon brand of “Free Soil” politics that birthed the black exclusion laws. But that is for another day.

Johnson’s anti-immigrant politics dove-tailed with the homegrown anti-radicalism in his district because Wobbly and Socialist politics largely rotated around ethnic lines. The socialist camps and community halls were also largely Norweigian cultural centers.

So, this brings us back to today in the post-2016 Southwest Washington. It may be too early to tell, but despite Washington being a safe state for Democrats statewide, we may see the cementing of a new conservative alignment in Southwest Washington this November. In fact, if Democrats can run the table everywhere else, but Republicans can keep the seats they’ve already won and possibly pick off an incumbent, I’d say that shift has happened. Also, I don’t think its too much to say that the energy at the top of the ticket in 2016 and 2020, with barely hidden anti-immigrant sentiment, is one of the reasons why.

There is a lot more to the regional political identity in Southwest Washington (and the broader Pacific Northwest) than anti-immigration politics. But reading The Red Coast reminds us that this isn’t a new evolution, but rather a part of the DNA that is just now finding new emphasis again.

I bought my copy at Browsers Books downtown. You should buy a copy locally as well.