A few weeks back I put up a selection of a longer piece about E.N. Steele I’ve been polishing. Here’s another portion of that longer piece, this one dealing with the idea of the lost aspects of his life. I was thinking about the portion when I heard about the Oyster House burning down this week.

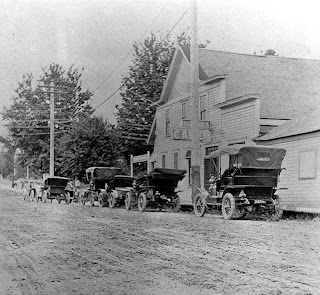

E.N. Steele became president and director of the chamber of commerce in the early 20s, and in 1925 he was elected as one of Olympia’s first city commissioners on a reform ticket. He served as one of Olympia’s inaugural planning commissioners and later as mayor. He was elected to the state legislature, and at least for awhile, served on a joint conference committee with young Warren Magnuson.

Of course, his most notable contributions was in the field of oysters. Owner and manager Oyster Company, Olympia 1907-1950; Rockpoint Oyster Company, Samish Bay, Washington 1922-1950; past president Pacific Coast Oyster Growers Association; past executive secretary Olympia Oyster Growers Association.

Steele also literally wrote the books on the shellfish industry through his life in “The Rise and Decline of the Olympia Oyster” and “The Immigrant (Pacific) Oyster.”

Here is the most significant lesson I take from my survey of E.N. Steele’s life:

Like his time as a lawyer defending Indians in treaty rights cases, Steele’s most significant and intimate details of his life are examples of how marks on history erodes. The craters in Washington State and Olympia of Steele’s time are practically gone for us.

For example, Steele’s largest contribution to our lives was writing the 1934 “Steele Act.” Until recently that law would rule how liquor was regulated in Washington State. As Washington State looked for a system to manage alcohol following the end of Prohibition, Steele worked with a University of Washington professor to create the system of laws that would remain on the books for almost 80 years. The system of state run stores and a Liquor Control Board was in force until 2010 when it was overturned by initiative.

Second, the Olympia neighborhood where the Steele family lived for years does not exist. The city blocks that now make up the east capitol campus were drawn off the map in the early 1960s. The corner of 14th and Franklin where the Steeles lived is somewhere north of the Department of Transportation Building and above a massive parking garage in the east capitol campus.

The street Steele looked out every morning now runs underground before joining Capitol Way. Evidence of the middle class neighborhood, which featured the city’s second high school and small lots with craftsmen homes can’t be found.

Even though we still have an Oyster House restaurant in Olympia on the site of an old shucking plant, the Olympia oyster is probably the faintest memory that made up Steele’s life. The shellfish that was so plentiful in our city that it was named after our city is practically gone from our bay. It barely even exists anywhere naturally in our local area.

In the “Rise and Decline of the Olympia Oyster,” Steele tracks the eventual death of the Olympia oyster industry and with it the last major sets of the species. The main causes of decline were Industrial pollution and development overtaking the oyster’s natural habitat. And, as evidenced by “Immigrant Oyster,” Steele’s book about the more resilient and foreign Pacific oysters, the shellfish industry simply moved on.

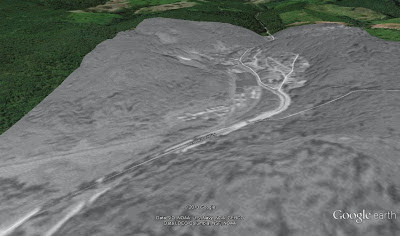

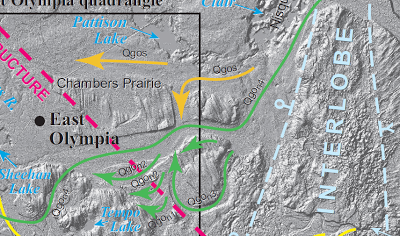

But, in Olympia, it was deliberate changes to our shoreline that erased the Oyster that was named for our city from our history. From Steele’s history of the Olympia oyster:

In Southern Puget Sound in the vicinity of Olympia. where they were most abundant.

In those days a wooden bridge crossed Budd Inlet near the location of the present concrete bridge to the Westside district. In honor of an early pioneer, it was called the “Marshfield” bridge. Chinatown was located south of this bridge, along the east shore. So, in territorial days the Chinamen took over possession of the oysters south of the bridge. North of the bridge and on both sides of the bay, the oyster beds were claimed by the Indians who had a village on the west side, just north of the bridge. The natural oyster beds south of the bridge are now covered by water due to the dam recently constructed to create a lake for capital beautification.

I’m not exactly sure why I focus on the things that are gone now when I look around Steele’s life. I was first drawn in because of the small details I picked up about him being a treaty rights lawyer. But, the Steele Act, his neighborhood and the Olympia oyster are there too for me.

Maybe its how we don’t write failure into our histories. We only focus on the things that ended up having an impact.

…

His book I cited earlier, “Letters from Grandpa,” is literally a series of letters from Steele to his grandchildren. Each chapter is a letter that tells a story about an episode in his life. The letters are peppered with “with love to you all” and “I love you all very much.” These aren’t words of a grandfather laying down regrets, but stories of a life well-lived.

But, we don’t think about the neighborhood we lost. We think about the natural growth of the campus, the modern office buildings naturally counterbalancing the traditional stone buildings across Capitol.

We also don’t think much about Olys at one point being picked where Capitol Lake is now. We can still buy little Olys from the Oyster House, though you aren’t sure where they’re picked from unless you ask.

.jpg)