One of my favorite weeks of the year comes at the end of June, when the Washington State Office of Financial Management releases its annual population estimates. This data dives deep into how cities and counties across the state are changing, whether through natural growth (births minus deaths) or migration.

It’s a treasure trove of information that offers valuable insight into how our communities and regions are evolving. Here are a few takeaways I’ve gleaned from this year’s release:

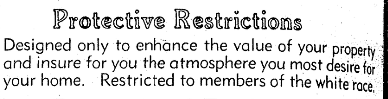

1. The death churn continues.

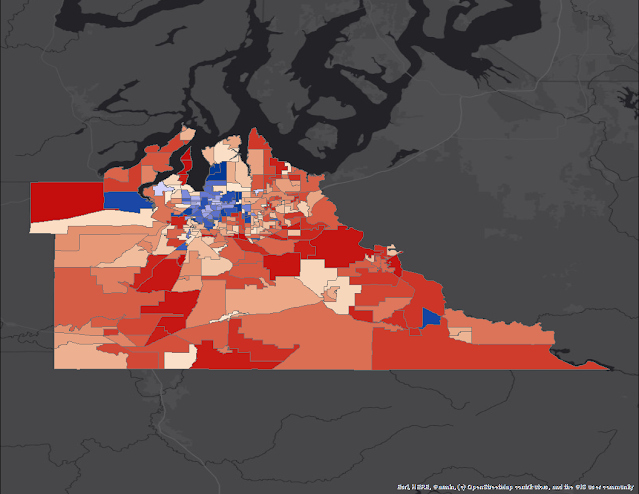

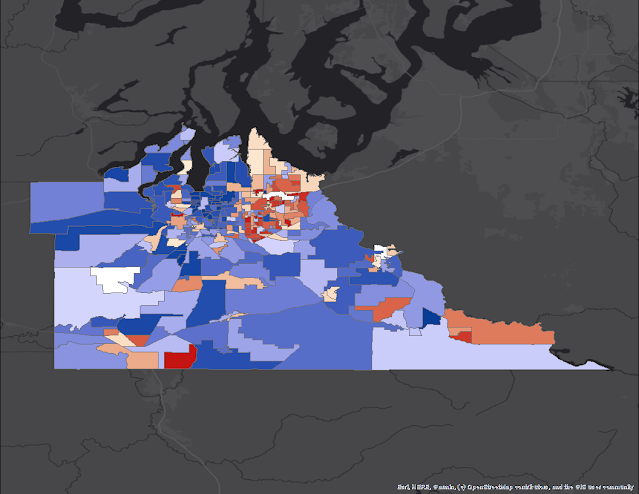

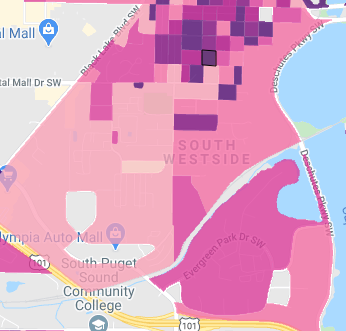

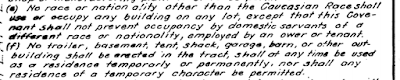

Over the past few years, I’ve noticed a growing trend in county-level data: many areas are now experiencing negative natural growth. That is, more people are dying than being born. I visualized this by zooming out and color-coding the data, Clallam County stands out as a long red line, while King and Pierce counties show up as long blue lines.

As time goes on, more counties are trending red. This doesn’t necessarily mean these counties are shrinking in total population (in-migration often makes up the difference). Still, it does show the demographic impacts of an aging population, particularly as the boomer generation continues to age.

Interestingly, this shift in natural growth isn’t uniform across the state. When I mapped the past few years of data, a pattern emerged: rural coastal counties like Clallam are at the center of this trend, while areas like Puget Sound and parts of Central Washington show different dynamics.

2. Migration offsets the death churn.

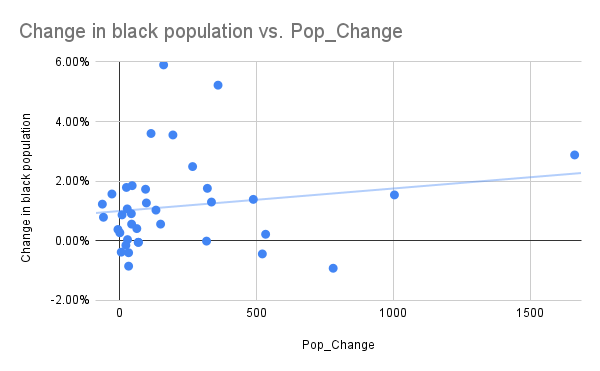

I also plotted natural growth against net migration since 2020 and found a clear inverse relationship: the more deaths outpace births, the more in-migration tends to make up for the gap.

And despite King County’s reputation as a hub for newcomers, it’s not actually the most migration-heavy area on a per capita basis. That distinction goes to counties like Pend Oreille, Columbia, and Pacific, all of which are seeing negative natural growth.

It raises a deeper question: Are these new arrivals older, potentially exacerbating the natural growth decline? There’s more to explore in this data in future posts.

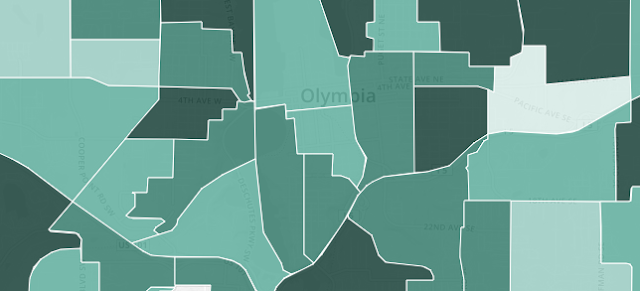

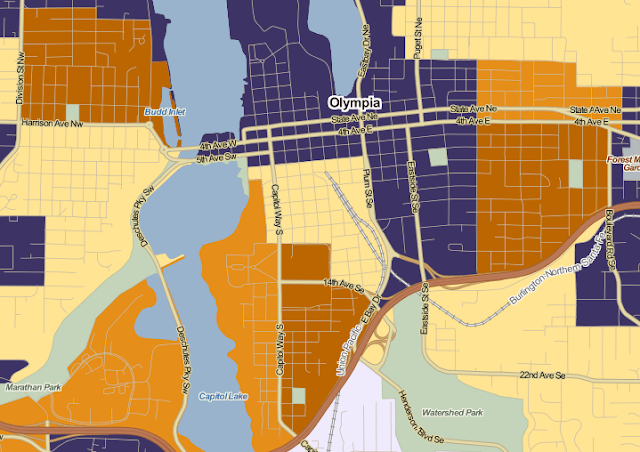

3. Thurston County: Lacey outpaces Olympia (again).

Shifting focus to Thurston County, the trend of Lacey growing faster than Olympia continues. Lacey remains the largest city in the county, with over 60,000 residents compared to Olympia’s 57,000.

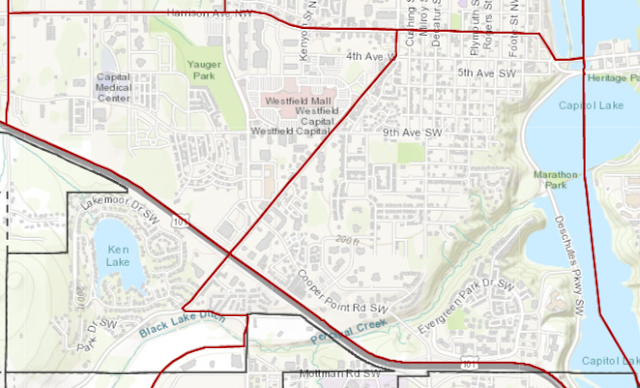

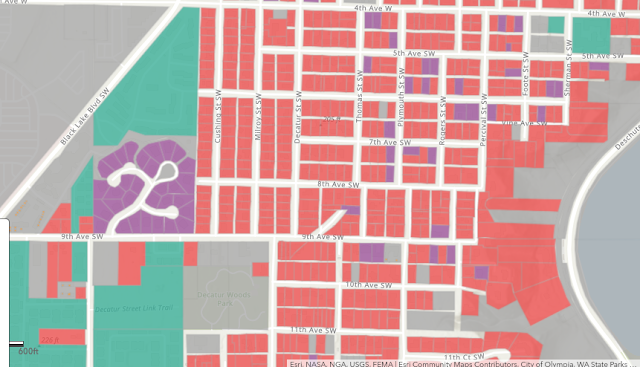

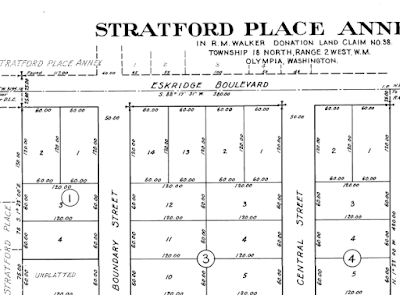

Looking at data from the Thurston Regional Planning Council, the reason is clear: annexation.

Since 2020, Olympia hasn’t annexed any new land, while Lacey has added more than 1,100 acres.

This expansion impacts population density. Although Lacey is still slightly more dense than Olympia, its density fluctuates year to year. Meanwhile, Olympia’s density has increased steadily.

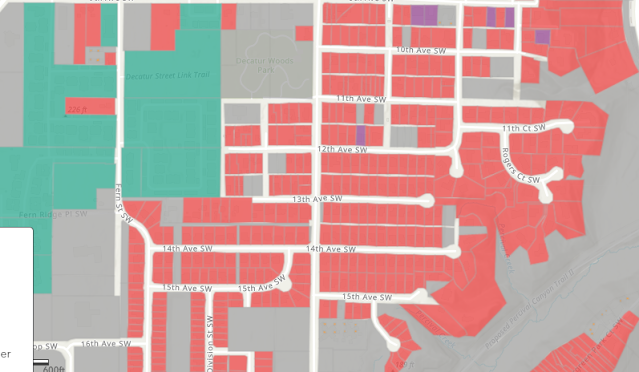

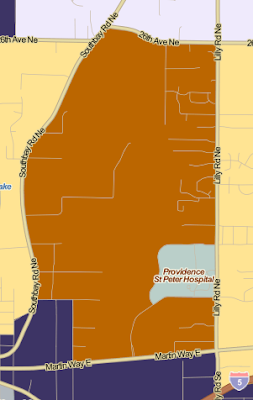

4. Tumwater and Yelm: Expanding outward.

Speaking of annexations, Tumwater and Yelm have also been aggressive in expanding their boundaries.

Since 1979, Tumwater has annexed over 7,000 acres, about the same as Lacey, and far more than Olympia’s 2,200 acres. Yelm, despite its smaller size, has annexed more than 3,000 acres.

This means that, physically, Tumwater and Yelm cover far more land than their populations might suggest. If Tumwater had the same population density as Olympia or Lacey, it would have between 55,000 and 57,000 residents. Yelm, too, would be much larger, north of 17,000 residents.

These shifting patterns of growth, migration, aging, and expansion paint a complex and fascinating picture of how Washington is changing, county by county, city by city. There’s a lot more to unpack, and I’ll keep digging into it in future posts.